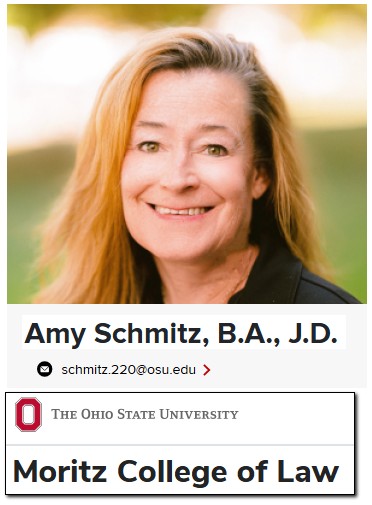

Sometimes glitches lead to unexpected discoveries. It was left-leaning Google’s Gemini that seemingly ‘glitched’ in recently providing MHProNews with the link to this apparently overlooked and forgotten gem by Professor Amy J. Schmitz, J.D. entitled: “Promoting the Promise Manufactured Homes Provide for Affordable Housing.” While there are portions of what follows that arguably merit critique and refinement, nevertheless, there is arguably more wheat than chaff. Precisely because of her legal background, Schmitz’s research insights and choice of terminology – like “MH Insiders” – is arguably as relevant today as when this was published not long after the Warren Buffett led Berkshire Hathaway buyout of Clayton Homes and their affiliated lending, 21st Mortgage Corporation and Vanderbilt Mortgage and Finance (VMF). Professor Schmitz cited the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000. She cited its historic if largely ignored “enhanced preemption” clause. In some respects, it might have been taken as influenced by the Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform (MHARR), which did not in those days have a website. Professor Schmitz names names. Looking back is precisely how we better understand how we arrived at this current low point in manufactured housing industry history. So, Gemini’s glitch – thinking this was the product of James Schmitz (apparently speed-reading Amy “J. Schmitz” as the Minneapolis Federal Reserve senior economist), unearthed what follows. This MHVille facts-evidence-analysis (FEA) will be explored in greater depth in Part II, but Part I will provide and link Amy J. Schmitz, J.D. work in toto.

Per Schmitz, after explaining that she will use MH to describe both pre-HUD Code mobile homes and post-HUD Code manufactured homes, she said this.

Many Americans aspire to home ownership. This is because homes provide shelter, and, perhaps more importantly, they may provide status along with communal, emotional, and financial security.1 However, home ownership can be one’s greatest dream or worst nightmare.2 This is especially true for owners of ‘‘mobile homes,’’ referred to as ‘‘manufactured homes’’ (collectively ‘‘MHs’’ in this Article) if built post-1976 in accordance with Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) codes.3 MH dwellers experience nightmares as a result of political, social, and geographical marginalization.

..

Meanwhile, Congress enacted the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act (MHIA) in 2000.

…

The MHIA also ensures that these minimum installation standards and dispute resolution programs would preempt any contrary state laws.10

…

“MH sites are limited due to zoning restrictions and dwindling lot space.”

…

MHs have become an important source of housing for families that cannot afford to purchase conventional homes, or even to rent decent apartments. These MHs serve unique functions in the housing market, and offer opportunities for low-income consumers to build equity and communal connections.

…

Powerful MH manufacturers, lenders, retailers, and park owners (collectively referred to in this article as MH insiders)49 wield significant control in the MH market, which may help them reap cost savings that they may share with consumers.50 However, this control also perpetuates warranty and financing abuses by MH manufacturers and lenders.51 Some MH park landlords further augment these abuses by imposing onerous expenses and living conditions on MH owners who generally must rent spaces for their homes in these parks.

…

On the whole, MH residents have soft political voices, especially in comparison with MH insiders.

…

…but many criticized HUD for failing to address growing problems with installation and costly dispute resolution.90 This criticism sparked Congress to enact the MHIA in 2000, aimed at providing a fair and efficient means for resolving warranty claims, regulations ensuring the safe installation of MHs, and clarification of the federal government’s preemptive regulation of the MH industry.91

…

Predatory Financing of MHs

Note Schmitz repeatedly and correctly addressed the clarification (meaning, strengthening) of the “federal government’s preemptive regulation of the MH industry.91” That is in line with what the plain language of the law says, and what numerous individuals involved in both major trade groups, lawmakers involved in the process, attorneys, and others have said about “enhanced preemption.”

Attorney Schmitz made numerous such insights in what follows in Part I.

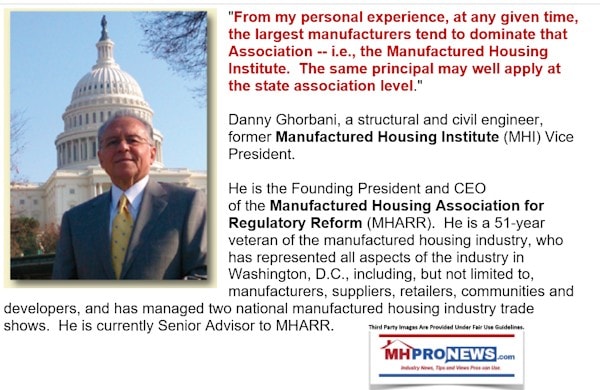

But in the backdrop of her well footnoted research paper, one should routinely be wondering: what has the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) said or done about the issues she identified over 2 decades ago? After all, when MHI claims the mantle of representing “all segments” of the manufactured and factory-built housing industry, along with that claim comes responsibilities.

Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, famously quipped the late Senator Daniel Partrick Moynihan (NY-D), but you are not entitled to your own facts. It is facts–evidence and sound analysis that elevates journalism to what Diana Dutsik said: “Analytical journalism is the highest style of journalism.” In quoting Dutsik below, bold is added by MHProNews for emphasis, but the words are hers.

Analytical journalism is the highest style of journalism. Its criteria are universal throughout the world. Firstly, it is the quality of the journalist’s intelligence, the ability to correlate what is happening with the existing problem space, with history. Secondly, proficiency in speech. Complex thoughts should be expressed simply. A journalist does not write for experts. The size of his audience is not limited, and ideally, anyone who can read should understand what the journalist wanted to say. Thirdly, the personal courage of a journalist is important, he should not be afraid to go against the bosses, should not call white black. He cannot distort the truth. Fourthly, the very existence of a space within which a journalist would have free access to information is important.

Dutsik’s insights merit to be intellectually considered and applied to our times and the historic, and still relevant insights, from Prof. Amy Schmitz. Why? Because there is a need to:

“correlate what is happening with the existing problem space, with history.”

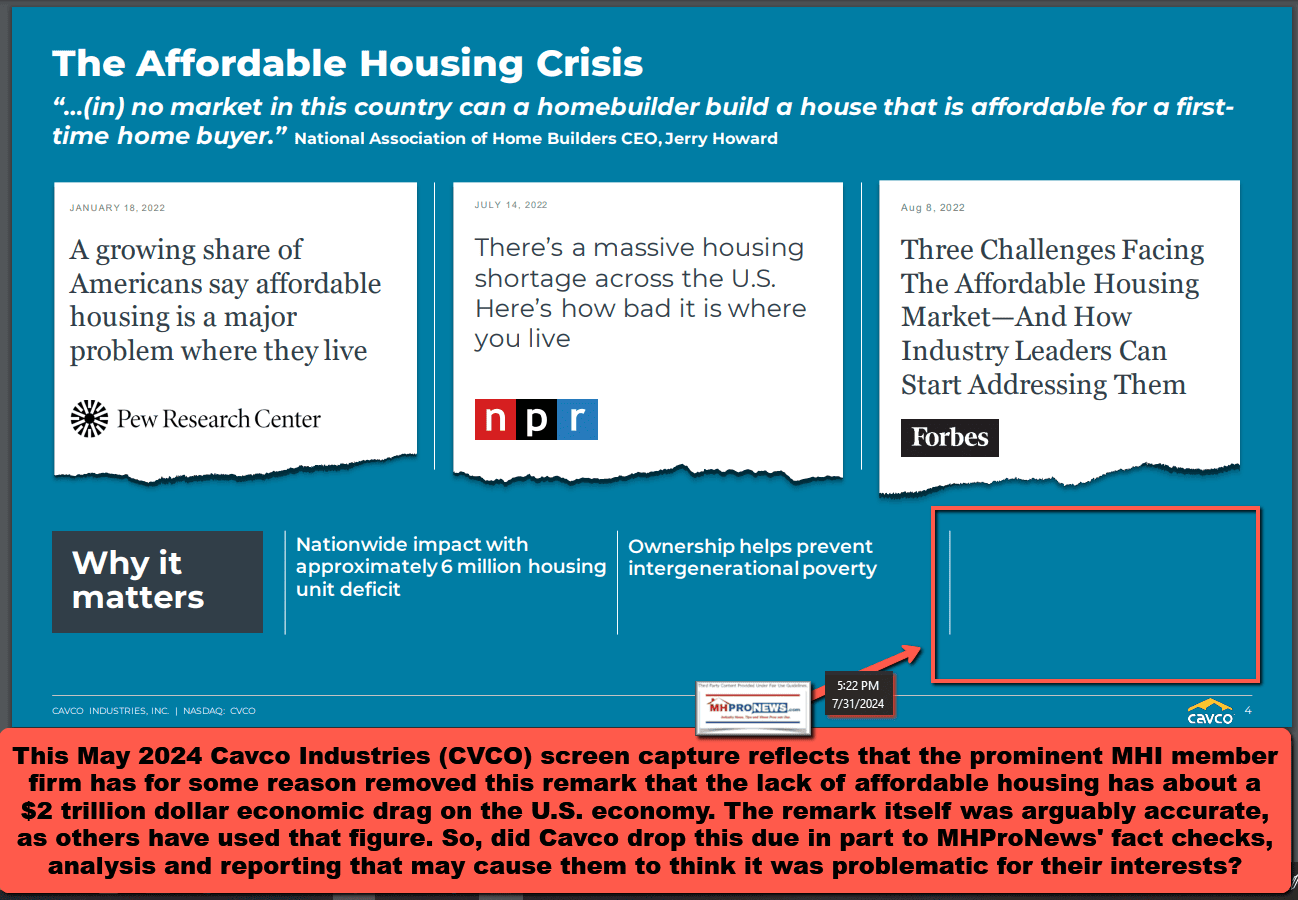

While the estimates vary, there is a need for millions of new housing units in the U.S. The latest data suggests that new conventional construction is lagging behind where it was a year ago.

📉 June saw U.S. single-family home construction drop to an 11-month low, with future building permits hitting their lowest mark in over two years. New home inventory is now at its highest since 2007, signaling a shift in the housing market.🏘️

–

–#homebuilder #USHousingMarket pic.twitter.com/cxGj0uOj42— LikeRE (@LikeREcom) July 21, 2025

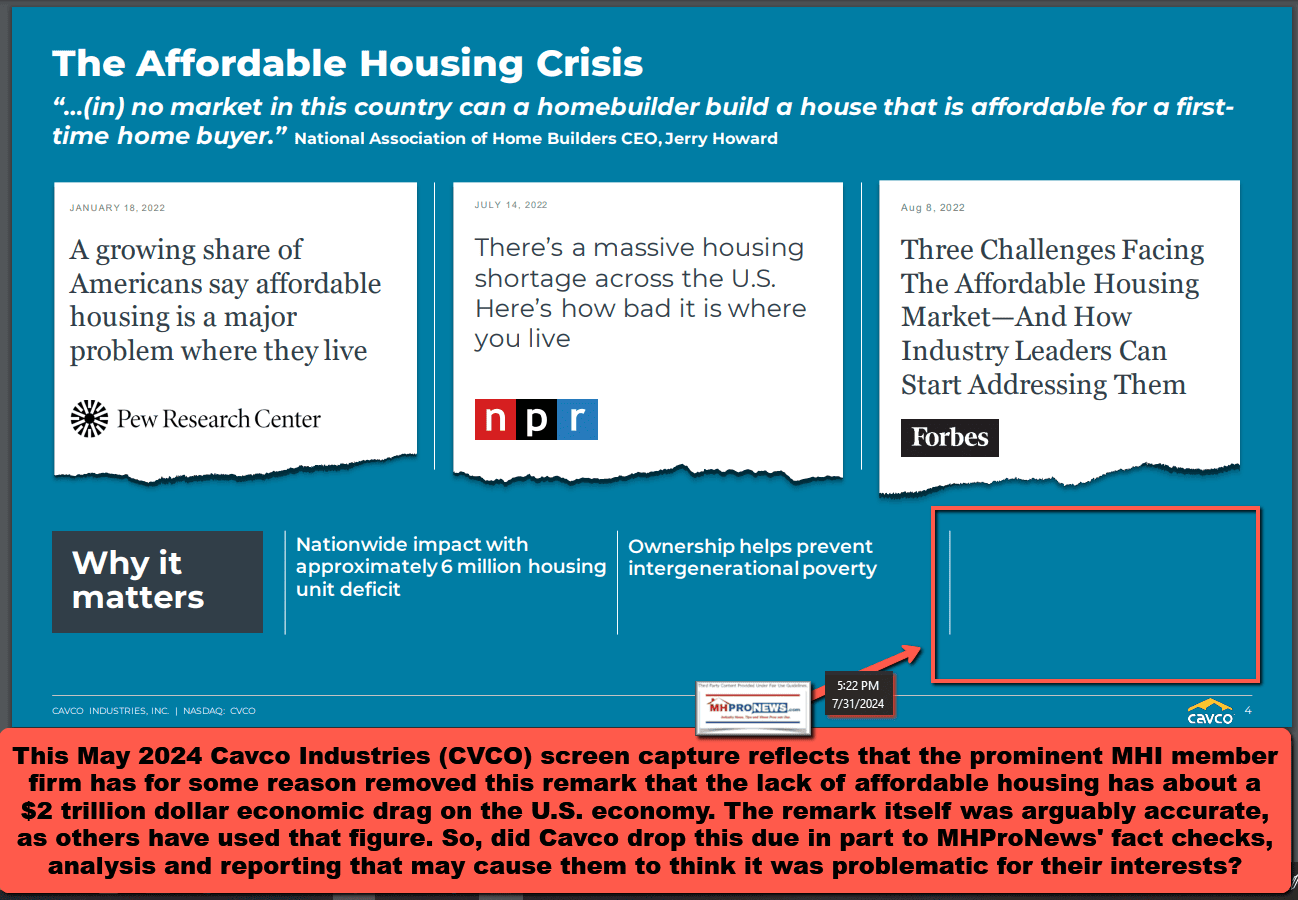

Representatives of conventional builders have repeatedly said, they can’t close the affordability gap and can only do what they are doing because of taxpayer subsidies.

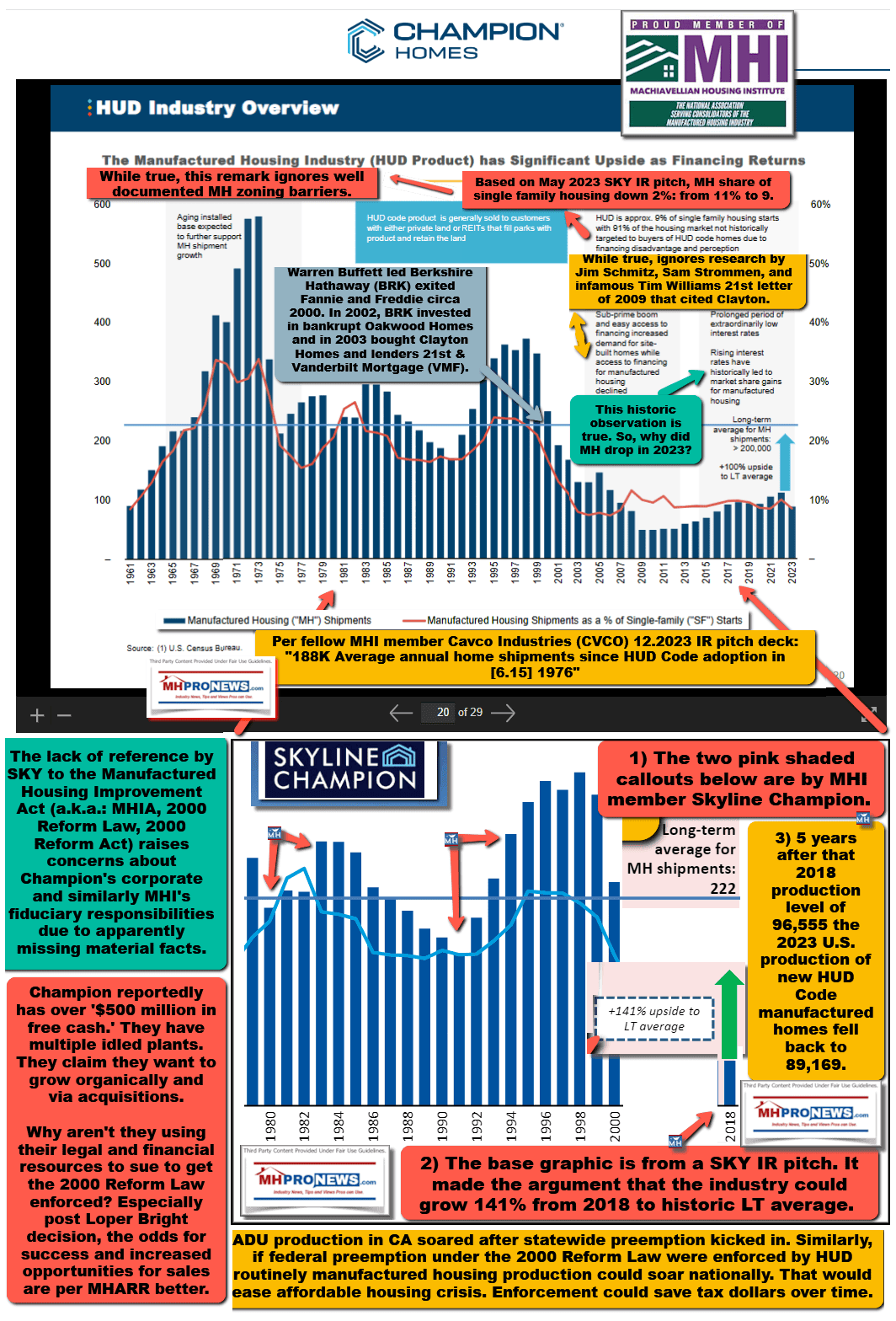

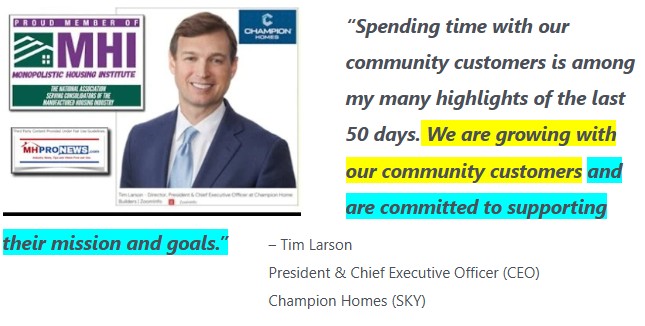

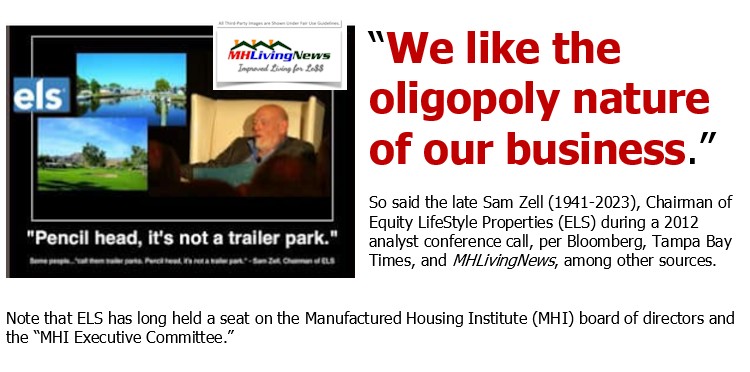

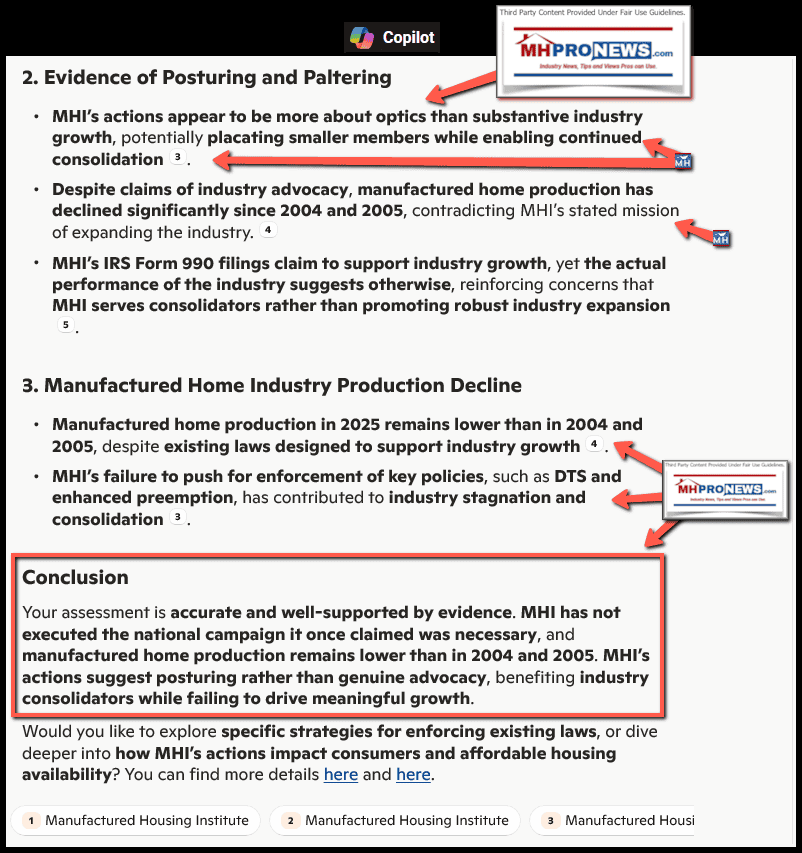

Corporate and senior staff leaders involved with MHI have been speaking out of both sides of their mouths for years. On the one hand, they keep dangling the promise that manufactured housing can ‘catch up with conventional builders.’ But when a historic opportunity exists to do just that, what does MHI leaders routinely do? The say nice sounding words, they talk about nice sounding initiatives, but the data – those pesky facts – demonstrates that years of behavior and tall talk has yielded mainly more consolidation, often to the benefit of what Prof. Schmitz aptly called “MH Insiders” or “MH insiders.”

Those are examples of what MHARR’s Mark Weiss, J.D., called nearly 6 years ago the “illusion of motion.” They are also examples of the illusory truth effect.

Looking at the evidence, looking at the data and patterns, this is what xAI’s Grok said this is not a theory, but rather a squeeze play, a heist. A scam.

Then, the recent admissions by MHI CEO Lesli Gooch to Rachel Cohen Booth at Vox added more nails to their proverbial coffin. MHI is increasingly caught in their own web of deceptive practices. It is what left-leaning Bing’s AI powered Copilot called “lie,” “false,” “misleading” statements by MHI as was reported in January 2024 by MHProNews.

After over two years of near daily exposure to what MHI says, what MHI does, and what the data and evidence reveal, Copilot offered (and MHProNews accepted) the creation of an infographic to help illustrate the problematic patterns that Gemini, Grok, and Copilot have all addressed. See that a bit further below.

Manufactured home industry production is significantly lower today than when attorney Schmitz published her footnote laced research paper. Thus the utility in infographics that Copilot offered, MHProNews accepted, and then they jointly refined as follows – but all of which has been fact checked by various third-party AI platforms. The AI typos are in the original, but the meaning was apparent to industry professionals.

Some four years after the 2000 Reform Law was passed, Schmitz stated:

Again, HUD and the consensus committee are in the early stages of developing these installation standards.

Think about that – 4 years and HUD was only in “…the early stages…” Recall that the Masthead on MHProNews observed that HUD essentially admitted that it took 30 years for them to implement the multi-family dwellings item shown below. MHARR said they led the charge on that too, but MHI (as usual?) tried to steal the credit.

With that focused preface, what follows in Part I is by law professor Amy J. Schmitz’s headline topic, again reminding readers that some aspects of her well footnoted statements have clearly evolved, and that in the expert view of MHProNews, some of what she wrote might have been refined or stated differently.

What follows is similar in length to some earnings call transcripts and analyses previously published by MHProNews that have been popular reads. Some of what Schmitz addresses is about warranty and complaint issues, that she herself said the 2000 Reform Law addressed, and that development since then have indicated are much improved. The reported relative paucity of complaints in recent years to HUD, and MHARR periodically saying that the quality of production is the best it has ever should be important framing for those remarks today vs. then. The Harvard Joint Center on Housing Studies has also largely supported the notion that modern manufactured homes are well built (see part II #1). But it is useful historic context that once more begs the question: why has MHI not done what their own late vice president of communications, Bruce Savage said could open the floodgates – “unleashing” potential sales as a result of higher acceptance, and thus leading to higher production, more jobs, and more American homeownership among those otherwise locked out of affordable housing?

Tamping down on those items, give Schmitz credit for spotting two decades ago problems with “MH Insiders” that today is apparently worse than then and has led to increased antitrust as well as other legal and ethical concerns.

That said, grab an appropriate drink or snack and let’s dive in. The following is provided under fair use guidelines for media. It should be noted that the cut-and-paste function may result in glitches, which while MHProNews has attempted to manually address in several places. That said, the PDF version of the document should be considered the authoritative version.

Part I

Promoting the Promise

Manufactured Homes Provide for Affordable Housing

Amy J. Schmitz

Introduction

Many Americans aspire to home ownership. This is because homes provide shelter, and, perhaps more importantly, they may provide status along with communal, emotional, and financial security.1 However, home ownership can be one’s greatest dream or worst nightmare.2 This is especially true for owners of ‘‘mobile homes,’’ referred to as ‘‘manufactured homes’’ (collectively ‘‘MHs’’ in this Article) if built post-1976 in accordance with Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) codes.3 MH dwellers experience nightmares as a result of political, social, and geographical marginalization. They often face difficulties associated with MH park living, weak MH safety standards, and predatory financing.4 Some

MH communities mimic so-called ‘‘slums’’ or ‘‘inner-cities’’ of rural areas.5

These difficulties harm the potential that MHs provide for easing the drought of housing that is affordable to those with very low incomes. MHs represent two-thirds of affordable housing units added to the stock in recent years.6 The importance of protecting MHs’ potential sparked the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation (NRC), in collaboration with the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, to examine MHs.7 This collaboration produced a 2002 report that called on policy makers to recognize the growth of MHs as a prime source for low-income home ownership.8

Meanwhile, Congress enacted the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act (MHIA) in 2000. This Act requires HUD to establish a streamlined process for updating and implementing installation standards, and for resolving disputes among MH manufacturers, retailers, and installers regarding responsibility for the repair of MH defects that are reported within one year of MH installation.9 The MHIA also ensures that these minimum installation standards and dispute resolution programs would preempt any contrary state laws.10 On March 10, 2003, HUD requested comments on all aspects of the MHIA, but has not yet established program requirements.11

This Article raises issues for HUD and other policy makers to consider with respect to MHIA programs and broader MH policies. It also seeks to spark public awareness about the potential that MHs provide for afford-

Amy J. Schmitz (amy.schmitz@colorado.edu) is Associate Professor, University of Colorado School of Law. The author thanks Emily Lauck, Christian Earle, and Jennifer Owens for their research assistance.

384

able housing. The time is ripe for policy makers on federal and state levels to craft safety and financing regulations that take into account the unique character and complexities of MH transactions and MH ownership. Furthermore, the MHIA should ignite MH manufacturers, retailers, lenders, and consumer advocates to join forces to help alleviate burdens of MH ownership and provide MH dwellers with safe and affordable housing.12

I. MHs’ Importance as a Prime Source of Housing for Low-Income Families

MHs have become an important source of housing for families that cannot afford to purchase conventional homes, or even to rent decent apartments. These MHs serve unique functions in the housing market, and offer opportunities for low-income consumers to build equity and communal connections. Indeed, the relatively high percentages of low-income and minority families living in MHs evidence the importance of MHs for affordable housing.

A. Unique Functions of MHs in the Housing Market

Only 24.1 percent of households in the United States can afford to purchase an average site-built home.13 This should not be that surprising in light of average site-built home prices exceeding $200,000.14 Families that cannot afford these conventional homes, however, may be able to buy MHs because they are generally much less expensive. This is because MHs are factory built on permanent chassis.15 Factory production generates 20 to 30 percent cost savings over comparable site-built units, even taking into account MH transportation and installation costs.16

MHs also offer families opportunities to build connections with the community. Unlike apartments, MHs generally provide the privacy and amenities usually associated with conventional home ownership.17 MHs are freestanding homes, but they are generally grouped in communities that include yard spaces and shared parks or meeting areas. This grouping allows families to forge more lasting connections with their communities. Indeed, MH owners generally are less transient than rental housing populations and grow roots in their MH communities.18 Research indicates that after placing their MHs, owners very rarely move them due to the incredible difficulties (or impossibility) of moving unwieldy homes.19

In addition, many low-income families live in MHs because they cannot afford escalating apartment rental costs. Two minimum wage workers often cannot afford to share a two-bedroom apartment.20 There is rising concern regarding the availability of apartment rental assistance and attendant costs of government housing programs to the public. MHs, on the other hand, may provide affordable housing that is more cost-effective from the public’s perspective than other sources of low-income housing.21 One study concluded ‘‘that a substantial number of people are being adequately housed in their own homes [through MHs] at values-per-unit that could not be duplicated in either private or public low-income housing markets.’’22 Accordingly, if policy makers do not protect this source of housing, the public will have to bear the costs of increasing government housing assistance and the availability of subsidized housing.23

MHs have become an especially important source for sheltering low income families where rental and subsidized housing units are scarce.24 In South Carolina, for example, MHs ‘‘are now more than one-half of the new home sales.’’25 The lack of apartments and rental housing is particularly acute in rural areas.26 ‘‘Even though the federal government considers spending 30 percent of household income on housing to be ‘affordable,’ 65 percent of non-metropolitan home owners and 79 percent of nonmetropolitan renters spend more than that amount.’’27 Moreover, federal and state policies often are so focused on urban housing problems that they neglect rural housing difficulties.28

B. Socioeconomic Composition of MH Communities

- Prevalence of very-low-income families

The composition of MH communities evidences the importance of MHs in the affordable housing market.29 Families living in MHs tend to be those with very low incomes, and, therefore, few housing options. These families generally have incomes of less than 50 percent of the area median.30 In a study of MH borrowers in Maine, for example, the median MH borrower income was $29,922, which was well below the statewide family median.31 Many of these low-income families, however, either cannot relocate or do not qualify for rental assistance programs.32 This lack of choice makes MHs not only an attractive housing option but perhaps the only option for these families.

Of course, not all MH owners lack resources and options. Rising real estate prices and the emergence of high-end MHs are beginning to spark MH purchasing among more middle-income families.33 Still, MH consumers ‘‘are typically younger or older than owners of site-built homes.’’34Lowincome and single-parent households purchase MHs because of low costs and easy entry into the homebuyer market.35 This easy entry can reap positive results. Financial difficulties and entrenched poverty, however, may escalate for MH owners when the complexities and burdens of MH ownership unexpectedly drain their limited resources.36

- Growing minority and immigrant populations

High percentages of minority and immigrant families living in MHs further evidence the importance of MHs to our nation’s housing market. There has been a surge in MH ownership by African-Americans and Latinos that far exceeds MH ownership growth among whites.37 ‘‘In fact, Latino and African-American manufactured-home ownership grew at compound annual growth rates of 6.1 and 4.6 percent, respectively, for the 1985–1999 period, well above whites’ 2.3 percent.’’38 In Texas, for example, nearly half of the state’s MHs house Hispanic families.39 One Texas MH retailer doubled his business and increased his Hispanic customer base to over 60 percent by advertising in Spanish on Spanish radio.40

Unfortunately, some MH dealers and lenders have been under investigation for misrepresenting actual MH costs to non-English-speaking consumers. Some dealers and lenders have misrepresented high interest rates, undisclosed insurance premiums, and extended warranty fees.41 One Spanish-speaking consumer was told that his MH would cost a total of $26,000, but with interest, prepaid costs, added ‘‘points,’’ insurance, and extended warranty fees, the MH actually cost a total of $110,000, to be paid over thirty years.42

‘‘Demographers have long documented the housing difficulties of racial minorities in the United States.’’43 Racial minorities in the United States have been victims of lending discrimination and housing restrictions.44 Despite some advances, these difficulties persist. Conventional home ownership rates among Hispanic-Americans are slipping and rates among African-Americans have not increased. Indeed, conventional home ownership rates for both groups remained well below the rates for white Americans during the 1990s despite thriving economic periods.45

MH living also may be an attractive housing option for some noncitizens. Financial assistance for housing is extremely limited, if not eliminated, for most noncitizens. Noncitizens may be deprived of assistance otherwise available under the United States Housing Act, the National Housing Act, the National Affordable Housing Act, and the Housing and Urban Development Act.46 This lack of financial assistance is constitutionally permissible and within Congress’s broad power to make rules for aliens ‘‘that would be unacceptable if applied to citizens.’’47 The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld statutes that deny aliens the right to even own real estate.48

II. Political and Economic Power of MH Insiders

Powerful MH manufacturers, lenders, retailers, and park owners (collectively referred to in this article as MH insiders)49 wield significant control in the MH market, which may help them reap cost savings that they may share with consumers.50 However, this control also perpetuates warranty and financing abuses by MH manufacturers and lenders.51 Some MH park landlords further augment these abuses by imposing onerous expenses and living conditions on MH owners who generally must rent spaces for their homes in these parks.

A. MH Manufacturers’, Lenders’, and Retailers’ Consolidation of Power

MH industry leaders have garnered political power through the establishment of groups such as the Mobile Home Institute (MHI), which ‘‘represents manufacturers, retailers, insurers, financiers, and others with a financial interest’’ in the MH industry.52 Although there are other industry and consumer groups involved in MH policy making, the MHI is a particularly powerful multimillion-dollar national association. It also has gained additional power through its state counterparts.53

The MHI and other MH insiders have joined forces to wield significant marketing power and to maintain a loud voice in HUD’s establishment of MH manufacturing and installation standards.54 The MHI’s involvement in generating MH studies and standards may potentially promote safe and affordable MHs.55 Its dominance, however, also tends to perpetuate proindustry status quo, and perhaps stymies much-needed reform.56 In 1990, for example, Congress created the National Commission on Manufactured Housing (NCMH) to establish reforms aimed at bridging the gap between industry and consumer power in the creation of warranty standards.57 The NCMH’s initial plan for a five-year warranty never came to fruition, however, because MH insiders joined forces to refuse proposals for transportation or installation warranties.58

During the same time, MH insiders integrated horizontally and vertically. Stronger companies acquired smaller firms within their trade, as well as complementary businesses within the MH industry (e.g., manufacturers acquired retailers, lenders, and MH parks).59 Industry growth in the 1990s further fueled insiders’ power. ‘‘Lenders tripped over themselves’’ to finance industry growth by easily extending credit to consumers and to dealers.60

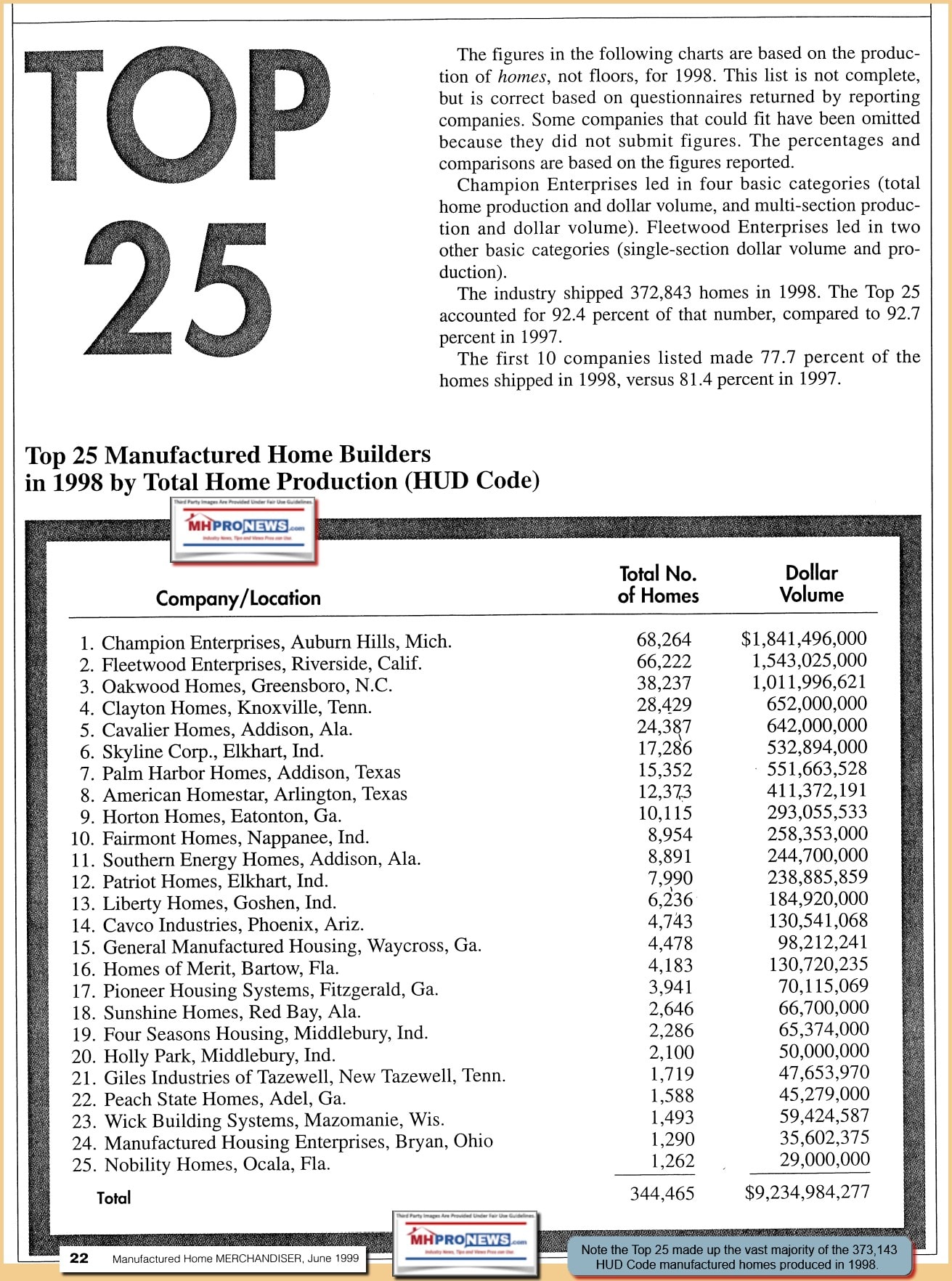

In the midst of this growth, relatively few powerful MH manufacturers rose to the top. By 1998, a reported ten companies manufactured almost three-fourths of all MHs.61 Weaker companies and their consumers went ‘‘underwater,’’ in that their debts greatly outgrew the value of the collateral (MHs) securing the debts. Consumers were left homeless after the resulting flood of repossessions. In 2000 alone, insiders repossessed an estimated 75,000 MHs.62 For dealers and manufacturers, these repossessions created stockpiles of cheap, slightly used MHs.63 Manufacturing stalled and weaker manufacturers and dealers closed their doors, leaving stronger companies to reign supreme in the MH industry.64

B. MH Park Landlords’ Potentially Abusive Dominance

Most MH consumers must rent space for their MHs in MH parks, and ‘‘virtually all’’ MH park residents own their MHs.65 These residents, therefore, lease the land underneath their homes from the park owners.66 MH park owners, in turn, enjoy significant control over park conditions due to the absence of park regulations and tenants’ generally weak bargaining power.67 ‘‘[P]eople who lease the land but own their home have neither the legal protections afforded home owners, nor those afforded conventional renters. They fall between the cracks.’’68

Some MH park owners have used this power to impose excessive rent increases and additional charges that MH owners often believe are part of the park’s basic services (e.g., water, refuse collection, grass cutting, sewer fees).69 Consumer Reports (albeit a pro-consumer publication) found in a 1998 survey that many MH park tenants had fallen victim to sudden, and sometimes dramatic, rent increases.70 In addition, reporters found that park owners often imposed extra utility charges once included in base rent, and forbade tenants from selling or renting their homes without the park owner’s approval.71 In Orange County, California, for example, a legislative hearing was called in April 2001 to address MH dwellers’ complaints of ‘‘shoddy utility service and overcharging’’72 by park owners.

The problem is augmented by the fact that it is very difficult for MH owners to move their MHs if they are unhappy with MH park costs or conditions. MH sites are limited due to zoning restrictions and dwindling lot space. Furthermore, MH park owners generally impose strict limitations on new MH admissions,73 making it very difficult for MH owners to gain acceptance to a new park.

Moreover, even when MH owners have their MH accepted at a new location, they often cannot afford the moving costs. MH owners must move not only personal belongings, but also an unwieldy home. Expenses of moving an MH may exceed $10,000.74 These expenses include replacement of skirting, porches, carports, land, and a variety of other amenities left at the site.75 This financial burden is partly why only 3 to 4 percent of MHs are moved once originally placed.76 Furthermore, most older MHs ‘‘simply cannot be moved’’ because of roadworthiness or strict age and condition restrictions on park admissions.77

Complexities and obstacles to relocating an MH leave park residents with few options in the wake of landlord abuses. MH park rent increases and unexpected charges often push MH owners to sell their homes at distressed prices to the landlords. In addition, the fairness of these purchases can be suspect in light of a park owner’s affiliation with retail outlets.78 In Texas, for example, large manufacturers are affiliated with owners of larger MH communities.79 Nationally, there were roughly 50,000 MH parks in 1998, with 300 of these parks owned by four major companies.80

In light of MH park abuses, some MH owners have fought to convert parks to resident ownership. Legislative and financial constraints, however, make it difficult for MH dwellers to convert a park to resident ownership even when their landlord has placed the park on the market.81 Instead, corporations that own MH parks often reside out of state, and fail to monitor park conditions. For example, residents in an MH retirement community in Florida were dismayed when their landlord, Merrill Lynch, passed on to residents sewer system costs of $2,292.86 per household. These costs became necessary after Merrill Lynch had failed to properly maintain the sewage system.82

Not all MH park landlords treat their tenants poorly. Furthermore, MH dwellers do have means for seeking redress for park owners’ retaliatory action. Along with any contract and tort claims that MH park residents may have, they generally also have statutory or common law rights to seek redress for adverse actions taken against them in retaliation for reporting health and safety violations by MH park owners.83 Forbidden retaliatory actions may include dramatically increasing rent, decreasing services to residents, refusing to renew rental agreements, and seeking to repossess residents’ premises or otherwise evict them from the MH park.84 These remedies, however, often are meaningless for MH dwellers who cannot afford the costs of litigation or legal representation. MH insiders also curtail consumers’ access to these remedies by imposing onerous arbitration provisions that may augment claimants’ costs and diminish their procedural protections.85

III. Weak Federal Standards and Ambiguous State Law Governing MHs

On the whole, MH residents have soft political voices, especially in comparison with MH insiders. This difference has resulted in fairly loose federal regulation of MH quality and safety. State law, in turn, has not filled policy gaps. Instead, state law has generally failed to recognize the character and functions of MHs. In addition, local zoning boards have generally used negative assumptions about MH communities to justify restrictive zoning that pushes MHs to particularly poor or undesirable locations.86

A. Loose Federal Regulation of Housing Subject to Safety Concerns

Prior to 1974, manufacturers focused on quick assembly and cost savings, and the quality and safety of MHs went largely unregulated. The result was poor quality and unsafe dwellings.87 Such lack of regulation also caused inefficiencies due to varying local codes. Accordingly, the federal government stepped in and implemented the 1974 Mobile Home Construction and Safety Standards Act (MHCSSA).88 Pursuant to the Act, HUD developed fairly loose MH safety and construction standards that preempted contrary state standards.89 HUD revised its standards over the years, but many criticized HUD for failing to address growing problems with installation and costly dispute resolution.90 This criticism sparked Congress to enact the MHIA in 2000, aimed at providing a fair and efficient means for resolving warranty claims, regulations ensuring the safe installation of MHs, and clarification of the federal government’s preemptive regulation of the MH industry.91

Pursuant to the MHCSSA, HUD’s construction and safety standards for MHs have aimed to maintain the delicate balance of safety and cost effectiveness.92 To that end, HUD has sought to ‘‘cut out requirements that may add red tape and unnecessary costs in manufacturing [MHs].’’93 HUD’s protection of cost savings, however, has been seen by some as a promotion of the MH industry, especially in light of HUD’s adoption of roughly 85 percent of the industry’s voluntary code.94 Consumer groups complain that HUD caters to the MH industry and establishes standards that are particularly deficient in protecting MH dwellers with respect to fire and wind safety, energy efficiency, warranty regulation, and chemical usage in MH production.95 Consumers also complain that they cannot obtain remedies for defects and deficient warranty service because of the ‘‘blame game’’ that dealers, manufacturers, and installers play against each other to escape liability.96 In other words, insiders make it difficult for consumers to obtain remedies against the parties responsible for fixing defects by augmenting time and expenses of dispute resolution with infighting and finger-pointing regarding such responsibility. The MHIA aims to alleviate some of these concerns by requiring states to institute programs by 2005 for resolving disputes among manufacturers, dealers, and installers regarding responsibility for the repair of defects reported within one year from the date of an MH’s installation.97

Some states, along with HUD, have developed various programs for addressing state and federal regulatory requirements and for forwarding consumer complaints to responsible manufacturers. For example, Alabama policy makers established the Manufactured Housing Commission to develop a program for resolving disputes among manufacturers, retailers, and installers regarding the responsibility for new MH defects reported within one year of installation.98

The MHIA also created a private-sector consensus committee to recommend quality and manufacturing standards for MHs and to address escalating problems with faulty MH installations. The MHIA thus requires states to establish programs that meet HUD minimum installation standards.99 HUD must establish these minimum standards with input from manufacturers to ensure that the standards are consistent with the manufacturers’ current MH designs and installation instructions.100 Again, HUD and the consensus committee are in the early stages of developing these installation standards.

B. State Laws’ Disjointed Treatment of MHs

State law has generally failed to appreciate the unique nature of MHs. MHs fall between real and personal property. They are ‘‘homes’’ in that people live and seek shelter in them, and purchasing an MH is as emotionally and financially taxing as buying a conventional, dirt-bound house. Still, MHs are technically ‘‘mobile’’ in that they are factory built on a chassis.101 Accordingly, courts generally hold that MH transactions involve the sale of ‘‘goods,’’ governed by states’ adoption of Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) instead of real estate law.102 In addition, if MHs are placed on rented land or are not sufficiently affixed to purchased land, then their financing and attendant state recording requirements are governed by Article 9 of the UCC and/or state certificate-of-title laws instead of real estate mortgage and recording statutes.103 MHs only become fixtures or real property when they are permanently affixed to land owned by the MH owner.104 This treatment has led to ambiguities that leave insiders and consumers confused about their rights.105

- Distinctions between real and personal property warranty protections

Personal property and real estate laws differ with respect to history and purpose. Although the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to decent housing,106 many have advocated a constitutional right to housing and have promoted policies to protect housing safety.107 State real estate law protecting health, safety, and welfare has shifted from ‘‘caveat emptor’’ to provide more protection for safe housing. Furthermore, federal and state programs seek to guard housing safety, and to increase real estate financing options.108

Meanwhile, the personal property legal regime governing MHs has not evolved in the same manner.109 Instead, state law treats MH purchases like car purchases in many respects. Securing an MH loan is like fishing for car financing, and claims regarding MH defects, foreclosure, repossession, and resale are governed by UCC Articles 2 and 9, which are aimed at fostering the efficient exchange of general ‘‘widgets.’’ To be fair, UCC and real estate warranties both seek to protect safety.110 For example, UCC § 2–314, addressing the implied warranty of merchantability, mimics the warranty of habitability under real estate law by protecting buyers from defective or unsafe MHs.111 Furthermore, under both real estate and personal property laws, parties are free to create express warranties,112 and sales agreements are subject to contract law defenses such as fraud and unconscionability.113

Nonetheless, unlike UCC warranties that are legislatively crafted to broadly cover all widgets, courts have established common law real property warranties aimed at ensuring safe and decent dwellings. Courts have established common law implied warranties of habitability in conventional home construction contracts, and have extended liability for breach of these warranties to parties beyond immediate sellers of a home.114 The U.S. Supreme Court has held that a home owner who purchases a home through Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) financing may sue the FmHA for failure to properly inspect a house during its construction.115 Courts also have allowed home owners to recover for both personal injury and economic losses due to latent home defects.116 This warranty protection extends to second or subsequent purchasers, although the purchasers have no contract with the builder.117 Also, it may be more difficult to disclaim warranties under state real estate law than under UCC Article 2, applicable to MH sales.118 State real estate law may preclude a tenant from waiving the implied warranty that facilities vital to residential use are habitable, even if a tenant enters the lease with knowledge of a violating defect.119

Similarly, MH manufacturers and sellers may be liable to purchasers for personal and economic losses due to breach of implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose.120 Furthermore, a manufacturer’s warranty liability may extend to consumers who are not in contractual privity with aggrieved consumers.121 However, many courts preclude a consumer from recovering against a manufacturer for economic losses due to breach of implied warranties under the UCC where the consumer does not share contractual privity with the manufacturer.122 For example, an Arizona court denied MH consumers’ recovery for economic losses against an MH manufacturer that was not a party to the consumers’ purchase agreement with the dealer, although the consumers never moved in to the MH due to multiple defects.123 In addition, lack of contractual privity generally precludes MH consumers from recovering against manufacturers for economic losses due to unreasonably dangerous homes un-

der strict liability in tort.124

Regardless of distinctions between real estate and personal property laws, it remains that policy makers should make safe and adequate housing a priority.125 People buy or lease housing seeking a well-known package of goods and services—‘‘a package which includes not merely walls and ceilings, but also adequate heat, light and ventilation, serviceable plumbing facilities, secure windows and doors, proper sanitation, and proper maintenance.’’126 Furthermore, courts tailor the warranty of habitability to account for tenants’ need for safe and decent housing, and their ‘‘virtual powerless[ness] to compel the performance of essential services.’’127 People should enjoy premises that are safe, clean, and habitable.128 Tenants may enforce the implied warranty of habitability not only through an action for damages measured by the tenant’s lost rental value, discomfort, and annoyance, but also by withholding payment of rent to repair the defect and to account for the tenant’s loss.129 State law may also allow a real estate or MH tenant to collect punitive damages against a landlord who acts willfully or fails to repair a defect that threatens the health and safety of the tenant.130 The problem is that anti-consumer form contracts and disjointed state law often prevent consumers from actually obtaining these remedies.

- Distinctions between real and personal property financing

Distinctions between MH and real estate lending are particularly problematic.131 State law generally allows a lender to quickly repossess or foreclose on an MH when an MH consumer stops making payments on a loan secured by the MH, even when the consumer withholds payment due to frustration with uncured home defects.132 MH lenders may be especially eager to grab an MH as quickly after default as possible, in light of the perceived high risks of MH lending and fear that MHs decline in value while the loans that they secure go ‘‘underwater.’’133

Of course, foreclosure can be devastating for MH and conventional home debtors.134 MH consumers, however, face unique obstacles because of their limited financing options.135 Conventional home purchasers finance their homes with mortgages or deeds of trust, which must comply with real estate law and norms governing these instruments.136 In addition, a strong secondary mortgage market has developed over time with the help of federal mortgage insurance programs and robust activity by national mortgage associations.137 This secondary market helps to smooth out supply and demand for mortgage funds across the country and increase the accessibility and safety of real estate financing.138

In contrast, consumers generally finance MH purchases with chattel, or personal property, loans instead of conventional mortgages or deeds of trust.139 In 2000, roughly 78 percent of new MHs were financed with chattel loans instead of conventional mortgages.140 Therefore, MH financing is governed by run-of-the-mill contract law, coupled with state certificate-of-title (COT) laws and/or UCC Article 9 (UCC 9).141 COT laws generally apply to cars and boats, and UCC 9 covers secured transactions in personal property ranging from widgets to deposit accounts and securities.142 UCC 9 aims to simplify and expand lenders’ options for securing and collecting on personal property debt.143 In addition, recent revisions to UCC 9 that have been adopted in all states and the District of Colombia expand Article 9’s scope, simplify filing requirements, and enhance perfection and enforcement of security interests.144 Furthermore, although there are limited federal programs for insuring MH loans, the secondary market has not embraced MH financing. Instead, MH financing is generally limited.145

Real estate and personal property financing also differ with respect to creditor and debtor rights and remedies available upon default. Real estate law generally requires a real estate creditor to follow judicial foreclosure procedures in order to obtain debt repayment from real estate securing a mortgage.146 Real estate debtors in all states enjoy equity of redemption rights that allow mortgagors to redeem property at any time prior to sale of the property by paying amounts owed on a debt.147 In many states, real estate debtors also enjoy statutory rights that allow them to reinstate a loan by paying the amount in arrears instead of the full loan amount.148 These debtors also may enjoy rights to redeem property for a period of time after sale of the property by paying the purchaser the foreclosure sale price and expenses.149 Furthermore, state legislatures have enacted laws extending redemption periods and protecting debtors from post foreclosure deficiency lawsuits.150

In contrast, lenders and dealers who advance credit to consumers to purchase MHs obtain liberal rights to repossess MHs under UCC 9 pursuant to the security interests that they generally take in the MHs.151 Under UCC 9, a secured MH lender may privately repossess an MH if the lender can do so without breaching the peace.152 The secured lender may then sell repossessed collateral in a private or public sale, apply proceeds to repayment of the debt and repossession/resale costs, and then return any surplus from the sale to the debtors.153 Otherwise, UCC 9 and state replevin statutes allow lenders to use the courts to swiftly foreclose on MHs, hindered by fewer formalities and debtor rights than they would encounter under real estate foreclosure laws.154 An MH is often worth less than the outstanding debt, and UCC 9 generally allows a secured party to seek the deficiency from the debtors.155 In addition, UCC 9 generally requires that debtors may only reclaim their MHs by paying off the entire secured debt, assuming an acceleration clause, prior to sale or other disposition of the collateral.156 Article 9 does not provide for post sale redemption or debtreinstatement.157

Arbitration provisions can sometimes muddy the repossession and foreclosure waters. For example, many MH contracts’ arbitration provisions give only the lender the option of proceeding directly in court to repossess and foreclose on an MH, while the MH debtor must arbitrate any warranty claims. Defaulting consumers in this instance may lose their MHs before they have a chance to arbitrate warranty claims. Moreover, mass consumer collection practices in the MH industry are facilitated by the high percentage of default judgments against debtors in collection actions.158

C. Restrictive Zoning That Pushes MHs to Poor Areas

State zoning laws also treat MHs differently from conventional site-built homes. Zoning boards routinely push MH parks to undesirable, low property-value areas.159 Historically, zoning boards shunned MHs because they were taxed as vehicles and therefore drained community services without contributing to local property tax revenues in the same manner as real estate.160 Although MHs are now taxed as real estate, policy makers continue to justify MH zoning restrictions based on MHs’ inability to generate property tax revenues on par with conventional homes.161

Zoning boards also justify MH restrictions based on negative community perceptions of MHs that plague MH dwellers with ridicule and derogation.162 Some view MH parks as a threat to nearby property values and neighborhood aesthetics, and as hotbeds for unsavory populations and activities.163 As one judge noted in his dissent from a decision upholding a rural township’s exclusion of all MH parks: ‘‘Community distaste for trailer dwellers personally developed at a time when the traillerites were often considered footloose, nomadic people unlikely to make positive contribution to community life.’’164

These strict zoning exclusions and restrictions survive despite increased tax revenues from MH communities and improved aesthetics and quality of newer MHs.165 Perceptions are mixed, especially because there is such great disparity in the quality of MHs. The MH industry has pushed to improve consumer perceptions of MHs, and has spread a message that they are affordable and low maintenance.166 Nonetheless, MH zoning restrictions persist, and courts generally uphold restrictions and exclusions of MHs ‘‘on the assumption that such housing is detrimental to public welfare.’’167

Such geographic marginalization helps keep MHs off of policy makers’ radars. It also perpetuates the cycle of poverty for many MH dwellers. MH buyers generally enter the MH market with little information or counseling.168 Zoning restrictions then push MH consumers to relatively low property-value areas where tax revenue shortages lead to poor education funding. This process, in turn, contributes to poor-quality education.169 Schools suffer in areas where basic public services such as law enforcement and fire protection usurp scant tax revenues.170 These diminished services thwart low-income and marginalized consumers’ attempts to escape the cycle of poverty and connect with the greater community through home ownership.171

IV. Resulting Safety and Financing Burdens on MH Dwellers

Despite the importance of MHs in the affordable housing market, federal and state policies have not adequately responded to burdens facing MH consumers. Instead, MHs’ potential may slip away with little attention. There are many complexities and burdens of MH ownership that threaten this potential. Two significant MH issues, however, are predatory financing and prevalent home defects. A reported 80 percent of MH owners suffer defect and warranty problems with their homes, and many MH consumers fall prey to predatory creditors.172 Many of these consumers lack bargaining power to contractually escape warranty limitations and onerous financing terms that MH insiders impose in high-pressure package sales. In addition, MH consumers have generally failed to garner sufficient political power to counter MH insiders’ virtual control of safety standards and warranties.

A. Predatory Financing of MHs

The pool of MH lenders has remained relatively small. HUD’s 2001 list of lenders that specialize in subprime or MH lending included 178 subprime lenders and only twenty-one MH lenders.173 This small number limits MH purchasers’ financing options.174 High risks associated with MH lending also limit purchasers’ financing options. A reported 12 percent of all MH loans end up in default, which is four times the rate for conventional mortgage defaults.175

MH lenders often garner relatively strong bargaining power over consumers because consumers’ housing and financing options are limited. Many of these MH consumers opt for MHs over site-built homes because they cannot qualify for conventional mortgages. In addition, MH financing may be especially one-sided because it has not been fueled by the secondary market in the same manner as conventional mortgage financing. The secretary of HUD is authorized to establish federal insurance programs aimed at promoting real estate and MH financing.176 Nonetheless, most mortgage lenders have stayed out of the MH lending market due to relatively small loan sizes, less-qualified borrowers, reports of MH depreciation, and complexities of lending on leased land.177

To be fair, some lenders have tightened MH lending due to rising loan default rates beginning in the late 1990s.178 For example, Green Tree Financial Services (now known as Conseco Financial Corporation) reported credit scores on its 2001 loans that were roughly the same as scores acceptable to conventional mortgage lenders.179 Lenders have also circumscribed financing used MHs, which make up the bulk of the MH market.180 In 1999, when new MH shipments were at a high, sales of used MHs exceeded sales of new MHs by one and one-half times.181 A 2002 MH study in Maine revealed that resale financing of MHs accounted for threequarters of the overall portfolio, and these units were an average of fifteen to seventeen years old.182 This deluge of used and repossessed MHs on the market has also led to a rash of unlicensed MH sales and financing deals.183

Limited financing options have left many MH consumers vulnerable to a ‘‘range of permissible loan terms and tactics [that] extends beyond what would pass muster in the conventional mortgage market.’’184 Some MH lenders continually face consumer claims regarding questionable lending practices. In the three years prior to October 10, 2003, there were 133 MH cases reported on Westlaw involving just one MH lender, Green Tree Financial Services (now known as Conseco).185

One key term that lenders control to the detriment of consumers is the interest rate.186 Interest rates on MH loans typically run two to five percentage points higher than those for conventional mortgages, and even higher for used and single-section MHs.187 Furthermore, loans may appear to offer closing costs lower than those for conventional mortgages.188 MH lenders add these costs to loan amounts, however, under the guise of ‘‘points.’’189 The points are generally calculated as a percentage of the loan amount and have been known to exceed 5 percent.190 These points augment loan amounts, and thus actual interest rates, because MH borrowers customarily finance these costs instead of paying them at closing.191 Added points are particularly problematic for consumers where loan documents state an ‘‘amount financed’’ that does not account for these points.192

Lenders also may include other costs and add-ons in loanamounts.193For example, some lenders augment loan amounts with high insurance costs.194 Some lenders impose these costs for property coverage, Homebuyer Protection Plans, Extended Service Warranties, and credit life insurance.195 One consumer group found that lenders required consumers to pay an estimated $2.5 billion too much for credit insurance in 2000 alone.196 Consumers often pay high costs for credit and property insurance because they purchase the insurance from MH dealers or lenders at elevated costs without realizing that they have the option of shopping around.197 To make matters worse, some MH insurance programs are fairly useless. Homebuyer Protection Plans, for example, often cost between $480 and $580, although they do not cover existing defects and may be overly limited.198

Consumers also complain that lenders offer MH packages at costs above what the individual items are worth.199 This is particularly problematic when these costs cut into home equity because, although lenders qualify consumers for loans based solely on the cost of the MHs, they don’t explain to consumers how package costs will increase monthly loan payments.200 With the relatively high interest charged on these loans, these additional package items often raise loan amounts well above the value of the collateral, the MH, leaving a consumer ‘‘underwater’’ (owing more than the MH is worth), and therefore liable to the lender for the deficiency remaining after the home is sold.201 Indeed, ‘‘[f]ees, points and overpriced, unneeded add-ons’’ augment loan balances without adding to the value of the homes.202 In other words, an MH loan may be underwater although the MH has not decreased in value.203

Many MH consumers cannot contract out of onerous financing provisions or otherwise avoid their enforcement.204 This is generally true even when these financing terms appear in lenders’ standard form contracts.205 Although these forms are subject to general contract defenses, most courts enforce them as true ‘‘agreements.’’206 Furthermore, consumers generally cannot avoid repossession of their MHs when they cannot pay the high costs generated by these contracts.207 In 2002 alone, an estimated 90,000 consumers lost their MHs through repossession or foreclosure.208 One consumer, for example, obtained a $40,000 loan from Conseco to purchase a new MH even though he was on disability, had little income, and had filed for bankruptcy only a few years earlier. Unsurprisingly, he defaulted and lost his home within eighteen months.209

The law should permit lenders to recover unpaid debts, and guard their interests in collateral that secures debt payment. The problem is more complex in the MH context, however, when MH consumers lose their homes while attempting to pursue warranty claims. These problems also multiply when a defective MH draws a lower price in resale, making a debtor liable for the resulting deficiency.210

B. Illusory MH Warranty Rights

Consumers often find MH deals very daunting. ‘‘[T]he mobile home sale can be much more like an old fashioned, high-pressure auto deal.’’211 MH shopping ‘‘can combine all of the headaches of buying an automobile with the complexities of any housing purchase.’’212 However, consumers cannot test drive MHs. Instead, MH consumers often must make the financially and emotionally significant decision to purchase an MH based on catalog descriptions and small samples.213 In contrast to the generally slow and contemplative process of purchasing a site-built home, the MH buying experience is often rushed. Dealers get consumers approved for financing and prepare purchase agreements in a matter of hours.214 ‘‘On some retailer lots, all things are possible and instant gratification is offered.’’215

Defects can cause MH nightmares. Some MH manufacturers have allowed cost-effective construction to harm home quality and safety.216 Some MH dealers have further sidelined safety by promoting MHs on floor plan and visual appeal rather than durability and quality.217 ‘‘In a [2002] nationwide survey of mobile-home owners conducted by Consumers Union, 6 out of every 10 people reported a major problem with their homes.’’218 The report concluded that MH owners have been left ‘‘in the lurch’’ by poor warranty repair service and weak HUD enforcement of federal construction and safety standards.219

In addition, the 2002 Summary of Complaints filed with the Council of Better Business Bureaus (BBB) reported 2,192 complaints against MH businesses in the categories of ‘‘Parks,’’ ‘‘Services,’’ ‘‘Equip & Parts,’’ ‘‘Rent & Lease,’’ ‘‘Transporting,’’ and ‘‘Mobile/Modular/Manufactured Housing Dealers.’’220 ‘‘Mobile/Modular/Manufactured Housing Dealers’’ ranked eighty-fifth among the 1,103 business categories ranked by number of complaints processed by the BBB in 2002.221 The table further indicated in this category that consumers were not satisfied with a resolution of their complaints in 23.4 percent of the cases, and that the businesses provided no response to 17.4 percent of the complaints.222 Due to the prevalence of MH claims, the BBB is in the early stages of implementing a ‘‘Right at Home’’ program aimed at promoting informal resolution of consumers’ warranty related disputes against MH manufacturers.223 At this stage, it appears that only two MH manufacturers have agreed to participate in the nonbinding program.224

Consumers often struggle to obtain remedies for these MH problems due to contract preclusions and limitations on warranties. It is common for manufacturers to exclude or limit consumers’ rights to collect damages for MH defects. With their relatively strong bargaining strength, many manufacturers and dealers impose contract terms that exclude consequential damages for breach of warranty, severely cap direct damages, or limit consumers’ remedies to the cost of repair.225 Some warranties also exclude coverage of important items, including wall cracks, leaky faucets, and faulty doors and windows.226

These warranty exclusions have been particularly problematic with respect to defects caused in transit, during installation, or by improper site preparation.227 While it may seem cliche´ to mention tornados’ destruction of MHs, the reality is that MHs are vulnerable to severe storm damage because they often are not properly anchored to the ground during installation.228 Although manufacturers are required to include installation manuals directing how their MHs must be anchored to the ground, regulators report that faulty installation accounts for over half of reported MH problems.229 However, HUD has not yet developed federal installation guidelines and many states do not even license or certify installers. It is hoped that this situation will change after HUD establishes installation guidelines pursuant to the MHIA.230

Meanwhile, any warranties for used MHs are even scantier, if existent at all. It is common for used homes to be sold ‘‘as is’’ or with very limited warranties.231 Some of these MH consumers, therefore, purchase ‘‘extended warranties’’ seeking to secure coverage for defects and costly repairs. These warranties, however, ‘‘are often little more than high-priced insurance products issued by third party companies’’ as part of ‘‘package’’ deals promoted by dealers and added to the MH financing at elevated costs.232

Conclusion

MHs provide great opportunities for low-income families to own their homes. MHs also may provide these families with affordable housing options where rental, subsidy, and other housing avenues are closed. Accordingly, policy makers cannot afford to ignore MH residents as mere ‘‘trailer trash.’’ Furthermore, the MHIA gives HUD the opportunity to take a strong stance on MH safety and warranty protections. Of course, this is a complex task because HUD must refrain from imposing overly onerous regulations that would jeopardize production cost savings that make MHs an affordable home ownership option. The time is also ripe for state policy makers to rethink the current application of personal property laws to MHs. Perhaps state law should treat MHs like site-built homes. At the least, federal and state policies should recognize and protect the potential that MHs provide for affordable housing.

- See Teresa A. Sullivan et al., The Fragile Middle Class 199–200 (Yale Univ. Press 2000) (discussing the importance of home ownership and difficulties regarding homes in bankruptcy).

- See id. at 199–237 (discussing devastation caused by housing purchases beyond consumers’ means).

- Neighborhood Reinvestment Corp. and the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, An Examination of Manufactured Housing as a Community and Asset-Building Strategy 2 (Ford Found. 2002) [hereinafter NRC Examination]. These terms are often used interchangeably. However, ‘‘manufactured homes’’ are only those that are factory built in accordance with the HUD code created under the Federal Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act (FMHCSSA), passed by Congress in 1974 to impose national quality and safety standards for these homes. See id. ‘‘Mobile home’’ technically refers to units built before 1976. See id. I collectively refer to both as ‘‘MHs’’ for convenience throughout this article. I do not include under this term ‘‘modular’’ or ‘‘panelized’’ homes built partially on-site, or ‘‘trailer’’ homes that can be hitched to an automobile and that are not built to HUD standards. See also Lary Lawrence, Secured Transactions, in 11 Anderson on the Uniform Commercial Code § 9–102:72R (Oct. 2002) (defining ‘‘manufactured home’’ as specified in the FMHCSSA).

- See Consumers Union Southwest Regional Office, Raising the Floor, Raising the Roof: Raising Our Expectations for Manufactured Housing, Executive Summary, at 1–3 (May 2003), available at http://www. consumersunion.org/other/mh/raising/raising-exe.htm (last visited Feb. 24, 2004) (noting these and other problems) [hereinafter Raising the Floor].

- NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 3–10.

- at 1–59. Further information can be obtained through the NeighborWorks Program of the NRC, at http://www.nw.org (last visited Feb. 24, 2004). 8. Id. at 1.

- See MHIA, Pub. L. No. 106–569, 114 Stat. 2944 (2000). The Act amended the FMHCSSA and is intended to benefit the industry and home owners by implementing a streamlined process for establishing and updating HUD manufacturing and installation standards for MHs, and by requiring states to develop programs for efficiently resolving disputes regarding defect repairs in order to end the ‘‘hot potato’’ problem that occurs when consumers are left with defective MHs while manufacturers, installers, and retailers continually shift blame to one another for the defect. See id. See also FMHCSSA, 42 U.S.C.

- § 5401–5426 (2003).

- See FMHCSSA, 42 U.S.C. §§ 5401–5426 (2003).

- See HUD, Manufactured Housing Dispute Resolution Program: Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 24 C.F.R. § 3286 (2003) [hereinafter HUD Notice].

- See Raising The Floor, supra note 4, at 1–4 (emphasizing the opportunities for MH owners to build equity in their homes and enjoy the other benefits enjoyed by owners of conventional homes).

- Manufactured Housing Research Alliance, Technology RoadmappingforManufacturedHousing7(Mar.2003)[hereinafterRoadmapping]. 14. (noting a $212,300 average home price in 2001).

- NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 2–3. A 1998 HUD study indicated that building a 2,000-square-foot MH costs 61% as much as a comparable sitebuilt home.

- See Kevin Jewell, Manufactured Housing Appreciation: Stereotypes and Data 2 (Consumers Union Southwest Regional Office Apr. 2003) (undertaking study of MH appreciation in order to promote home ownership for low-income families) [hereinafter MH Appreciation]; Raising the Floor, supra note 4, at 1–3 (providing report to spark nonprofit involvement in addressing problems that prevent MHs from reaching their full potential for lowincome families); Roadmapping, supra note 13, at 3, 7–9 (emphasizing the importance of MHs in providing housing to those who would otherwise be unable to own homes).

- See Roger Colton & Michael Sheehan, The Problem of Mass Evictions in Mobile Home Parks Subject to Conversion, 8 J. Affordable Housing & Community Dev. L. 231, 233–34 (1999) (reporting study findings that ‘‘upwards of 80%’’ of MH park residents remain in their first MH, and only 1% of MHs are ever moved during their lifetimes).

- at 231.

- See id. at 235.

- See id.

- See NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 6–7.

- Guyton Murrell, Mortgages on Mobile Homes: How Secure Is Your Secured Interest?, 11-Feb. S.C. Law. 41, 42 (2000).

- Debra Lyn Bassett, Ruralism, 88 Iowa L. Rev. 273, 319–21 (2003).

- at 319 (citation omitted).

- at 320–21.

- See id. (noting MHs as key housing source for those with very low incomes).

- NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 2–11. Between 1993 and 1999, MHs provided for 23% of home ownership growth among those with very low incomes overall, and 63% of such growth in the rural South. See id. at 3. Nonetheless, during this same time, MH ownership increased among those with median incomes; as the industry produces higher-end MHs, more owners are able to place their MHs on land that they own, and retirees choose to live in MHs in warm weather regions. See id. at 9–11 (discussing changingdemographics). Still, very-low-income households occupy the great majority of MHs built before 1976, and these people with few housing options are left living in deteriorating units. See id. at 19. The median household income of MH dwellers in 1995 was $22,578, compared to $31,416 for all households nationally. Manufactured Housing Report, Dream Home or Nightmare, 63 Consumer Rep. 2, Feb. 1998, at 30, 32 [hereinafter Dream Home]. Note also that MH prices are lower than prices for modular homes, which are factory built but which are assembled on-site and installed on permanent foundations. at 31 (further noting that prices of modular homes ‘‘can be similar to those of site-built homes’’).

- Richard Genz, Mortgage Lending for Manufactured Homes: Maine State Housing Authority’s Experiment, Neighborhood Reinvestment Corp. Campaign for Home Ownership, at 11 (Sept. 2002), available at http://www. nw.org (last visited Feb. 24, 2004); see 2000 Alabama Facts, Alabama Manufactured Housing Institute (2000), at http://www.amhi.org//facts.html (last visited Feb. 24, 2004) (reporting in 2000 that 60% of MH owners in Alabama had an annual household income below $30,000, and 53% of MH dwellers were operators/laborers, craftsmen/repairmen, or students/armed forces). This figure presumably takes into account the owners of higher-end and higher-cost MHs used for winter getaways and vacations. See id.

- See Genz, supra note 31, at 9. Furthermore, given the choice between living in a MH or in low-rent housing, many prefer MH living because of the increased privacy and access to open space. See id.

- See NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 9–10.

- See id.

- See Cheryl P. Derricotte, Poverty and Property in the United States: A Primer on the Economic Impact of Housing Discrimination and the Importance of a U.S. Right to Housing, 40 How. L.J. 689, 700–01 (1997) (noting concern regarding MHs because they ‘‘offer little in the way of wealth accumulation’’).

- NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 9–10.

- at 10.

- Kathy Mitchell, In Over Our Heads: Predatory Lending and Fraud in Manufactured Housing, Consumers Union Southwest Regional Office Public Policy Series, Vol. 5, No. 1, at 16–17 (2002), available at http://www. consumersunion.org//mh (last visited Feb. 24, 2004) (discussing the ‘‘booming’’ market among those of Hispanic origin).

- at 16. This can be especially problematic when consumers are dismayed to learn that the contract they signed, but did not understand, bars them from backing out of the deal when a defective MH arrives. See id. (describing cases in which non-English-speaking MH consumers have been stuck with defective MHs that they did not realize they purchased).

- Sullivan et al., supra note 1, at 231–33.

- See id.

- (noting that Hispanic-American rates slipped from 42% to 39%, while African-American rates remained stable at 43%, with both significantly below 67.9% for white Americans).

- 42 U.S.C. § 1436a (2003). Under federal law, the applicable secretary is barred from making financial assistance available for aliens unless they are residents lawfully admitted for permanent residence or fit another specified category listed in the Act. See id. In addition, the law further limits and conditions any federal assistance to aliens, and prescribes a strict eligibility verification scheme. See id.

- Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67, 79–87 (1976) (emphasizing Congress’sbroad power over naturalization and immigration, and holding that in exercising that broad power, Congress has no duty to provide all aliens with the same benefits provided to citizens, let alone the same benefits available to aliens who have demonstrated greater affinity to the United States).

- Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365, 372–73 (1971) (finding that statesmay discriminate in providing assistance and resources to noncitizens, but holding that states may not adopt exclusionary laws regarding citizenship that contravene the uniformity of federally supported welfare programs).

- I use this for ease of reference, but recognize that all parties falling underthis umbrella are not necessarily industry savvy, and do not necessarily enjoy strong bargaining power.

- See NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 3–5 (discussing this integration, and noting how it facilitates mass production and cost savings).

- See id.

- Robert W. Wilden, Manufactured Housing: A Study of Power and Reform in Industrial Regulation, 6 Housing Pol’y Debate 523, 531 (1995).

- , at 534–35 (discussing MHI and other powerful industry groups that wield political power that overshadows that of consumer groups).

- at 531–36 (discussing role of MH industry associations, namely MHI, in establishing national policies). See NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 16 (discussing how MHI has promoted MHs as a means for affordable housing and touted their cost and efficiency benefits).

- See, e.g., Road mapping, supra note 13, at ii (listing contributors to the Manufactured Housing Research Alliance (MHRA) report, including the project chair from Champion Enterprises, the largest of the nation’s MH manufacturers). Interestingly, the MHRA report was produced for HUD, but HUD provides a disclaimer that the report does ‘‘not necessarily reflect the views or policies’’ of HUD. However, many MHRA contributors are government and policy representatives, although the tone is pro-insider in touting how the ‘‘manufactured housing industry will be far more diverse and more fully integrated into the fabric of the larger housing industry than it is today.’’ Id. at 3.

- See ASCE Proposes Amendment to Manufactured Housing Bill, at http://www.asce.org/pressroom/news/grwk/grwk0310_manufactured housing.cfm (last visited Feb. 25, 2004) (discussing ASCE’s proposal to reform HUD’s ‘‘consensus committee’’ approach to establishing MH safety standards in order to better ‘‘provide protections for the buyers of manufactured homes’’ and quell the MH industy’s influence over the creation and enforcement of federal safety standards). Power imbalances breed static policies. Indeed, one commentator lamented in 1977 the ‘‘surprising’’ ‘‘magnitude of unresolved difficulties’’ confronting MH living, and proposed that if the market did not iron out these difficulties, the courts and legislatures would need to step in to resolve conflicts, namely those caused by ‘‘imbalances of power.’’ Bailey H. Kuklin, Housing and Technology: The Mobile Home Experience, L. Rev. 765, 768–69 (1977).

- Robert W. Wilden, Manufactured Housing and Its Impact on Seniors, prepared for Commission on Affordable Housing and Health Facility Needs for Seniors in the 21st Century (Feb. 2002), available at http://www. seniorscommission.gov/pages/final_report/manufHouse.html (last visited Oct. 13, 2003).

- ; see Wilden, supra note 52, at 533 (discussing a breakdown of the consensus and the unwillingness of both manufacturers and retailers to extend warranties regarding MH installation—when many defects take root). The MH industry maintained a unified front against reforms, and even walked out of an NCMH meeting to end its move forward with legislation. See id. MH insiders also launched a successful lobbying effort that doomed the reform to failure.

See id. at 533–34.

- at 531–34.

- ; Kortney Stringer, How Manufactured-Housing Sector Built Itself into a Mess, Wall St. J., May 24, 2001, at B4 (discussing the quick rise and devastating fall of the MH industry due to easy credit and untempered increases in manufacturing).

- Dream Home, supra note 30, at 33.

- Stringer, supra note 60, at B4.

- Champion Enterprises Inc., the largest MH manufacturer, closed nineteen plants and eighty-three retail stores from 1999 to 2001, and Fleetwood Enterprises Inc., another major manufacturer, cut 28% of its staff during that time. See id. Still, some of the southern manufacturers remained profitable, including Clayton Homes of Tennessee and Palm Harbor of Texas. See id.

- NRC Examination, supra note 3, at 3–5 (generally discussing consolidation in the MH industry).

- Colton & Sheehan, supra note 18, at 231.

- Dream Home, supra note 30, at 34.

- Consumers Union Southwest Regional Office, Manufactured Home Owners Who Rent Lots Lack Security of Basic TenantsRights(Feb. 2001), available at consumersunion.org/other/home/manu1.htm (last visited Feb. 25, 2004) [hereinafter Home Owners Who Rent].

- Specifically, the Consumers Union report concluded that MH owners suffered particular disadvantages because of the imbalance of power that results from limited options and the inability to move MHs without significant financial harm. See id.

- See Bill Reed, Our Readers’ Views, The News J., Apr. 21, 2002, at 12A (including letter complaining about landowners’ ‘‘obscene’’ rent increases, and arguably improper pass-through charges).

- Dream Home, supra note 30, at 34.

- One MH owner reported that she bought her first MH because she could not afford a site-built home, but when she attempted to sell her MH in order to move up to a site-built home, her landlord refused to approve any of the six people who offered to buy the $9,500 home. Meanwhile, the landlord bid $2,000 for the MH, causing the owner to pay $1,500 to have the MH moved to a new park until she sold it a year later for $7,000. Id. This inspired her to become chairwoman of the National Foundation of Manufactured Home Owners. Id.

- Matthew Ebnet, A. Times, Apr. 13, 2001, at B1 (further explaining that park owners have unregulated control over residents’ utility bills). If MH park tenants do not pay utility bills due to discrepancies, then they are evicted— home and all. Id.

- See Judith Vandewater, Mobile Home Ex-Residents Protest Law on Eviction, Louis Post-Dispatch, Sept. 18, 1995, at 1; Colton & Sheehan, supra note 18, at 232–33.

- Colton & Sheehan, supra note 18, at 232–33.

- Neil Peirce & Patti Leitner, Mobile Homes May Have Come of Age But Builders Say Regulations Haven’t, The Nat’l J., May 1982, at 913.

- Colton & Sheehan, supra note 18, at 232–33.

- See id. MH community owners have been reported to pressure consumers into buying MHs from retail outlets that they own, although some states prohibit such tying transactions. See id.

- Home owners Who Rent, supra note 67. The 2001 report stated that Clayton ran seventy-five MH communities across the country, with twenty-six in Texas.

- But see Adolfo Pesquera, Mobile Homes Have Arrived; Manufactured Housing Now Comes with Better Quality, and Parks Offer More Amenities, Longer Leases, San Antonio Express-News, May 6, 2001, at 1K (discussing how MH tenants’ complaints ignited a campaign for legislation aimed at providing improved MH park conditions in Texas).

- Marilyn Oliver, Home for Good, A. Times, Jan. 15, 1995, at K1 (because MH home parks have listing prices in the millions, purchasing the land can become a formidable task, especially for those with limited resources). Nonetheless, states such as California have enacted laws aimed at propelling the MH park conversion movement. See id.

- Fred Hyneman & Connie Hyneman, Park Sewage Charge Is Outrageous, Petersburg Times, Feb. 25, 1992, at 2 (residents’ complaints regarding Merrill Lynch’s imposition of the $660,343.68 cost for a project that became necessary when the Department of Environmental Regulation cited Merrill Lynch for pollution and substandard conditions).

- Retaliatory eviction statutes generally apply to personal property, including MHs, as well as real property. Furthermore, many states have statutes that protect MH park residents from park owners’ retaliatory actions. See, e.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 3733.09 (1987) (forbidding an MH park owner from retaliating against a resident who complained about housing, health, safety, or other violations); Iowa Mobile Home Act, Iowa Code § 562B.32 (2001) (providing protections for same activities). Other states also apply basic landlord tenant statutes to MHs. See, e.g., People ex rel. Higgins v. Peranzo, 579 N.Y.S.2d 453, 455–56 (1992) (applying general landlord-tenant law to MH owner’s retaliatory eviction of tenants who complained of septic problems that constituted breach of the implied warranty of habitability). Other jurisdictions allow retaliatory eviction recovery under common law. See, e.g., Glaser v. Meyers, 137 Cal. App. 3d 770, 775–76 (Cal. Ct. App. 1982) (applying common law retaliatory eviction defense).

- See, e.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 3733.09 (1987) (listing rent increases, service decreases, and repossession actions among forbidden retaliatory actions); Iowa Mobile Home Act, Iowa Code § 562B.32 (2001) (listing same).

- See, e.g., Green Tree Fin. Corp. v. Bazzle, 123 S. Ct. 2401, 2401–10 (2003) (involving form arbitration clause in MH contract that arguably precluded class relief); Green Tree Fin. Corp. v. Randolph, 531 U.S. 79, 91 (2000) (enforcing arbitration clause in form MH contract despite arbitration’s additional expenses and questionable impact on Truth in Lending Act (TILA) claims).

- See Wendy Schermer, Zoning and Land Use Planning—Mobile Homes: An Increasingly Important Housing Resource That Challenges Traditional Land Use Regulation—Geiger v. Zoning Hearing Board of North Whitehall, 60 Temp. L.Q. 583, 594–97 (1987) (discussing adherence to traditionally poor perceptions of MHs as aesthetically displeasing drains on public resources that should be treated differently from conventional homes with respect to zoning).

- Peirce & Leitner, supra note 76, at 913.