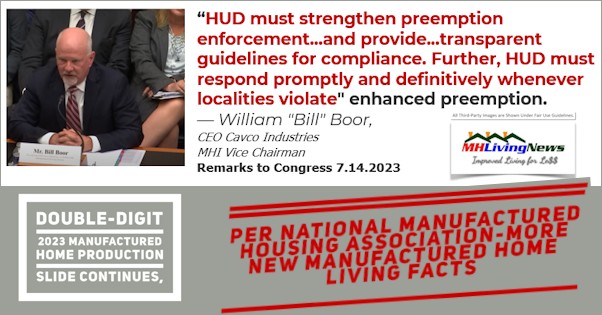

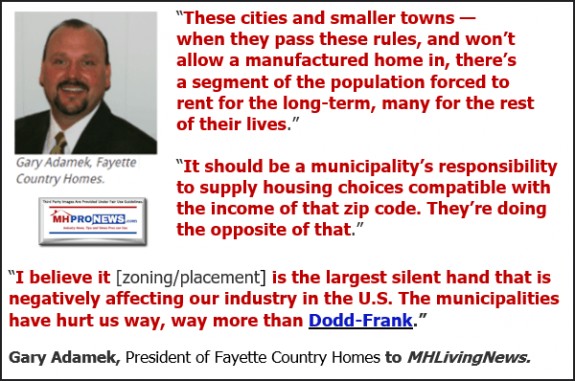

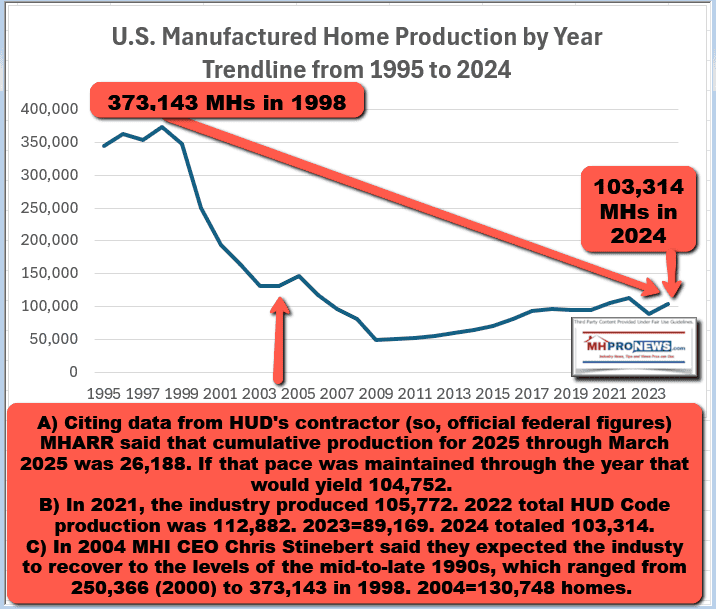

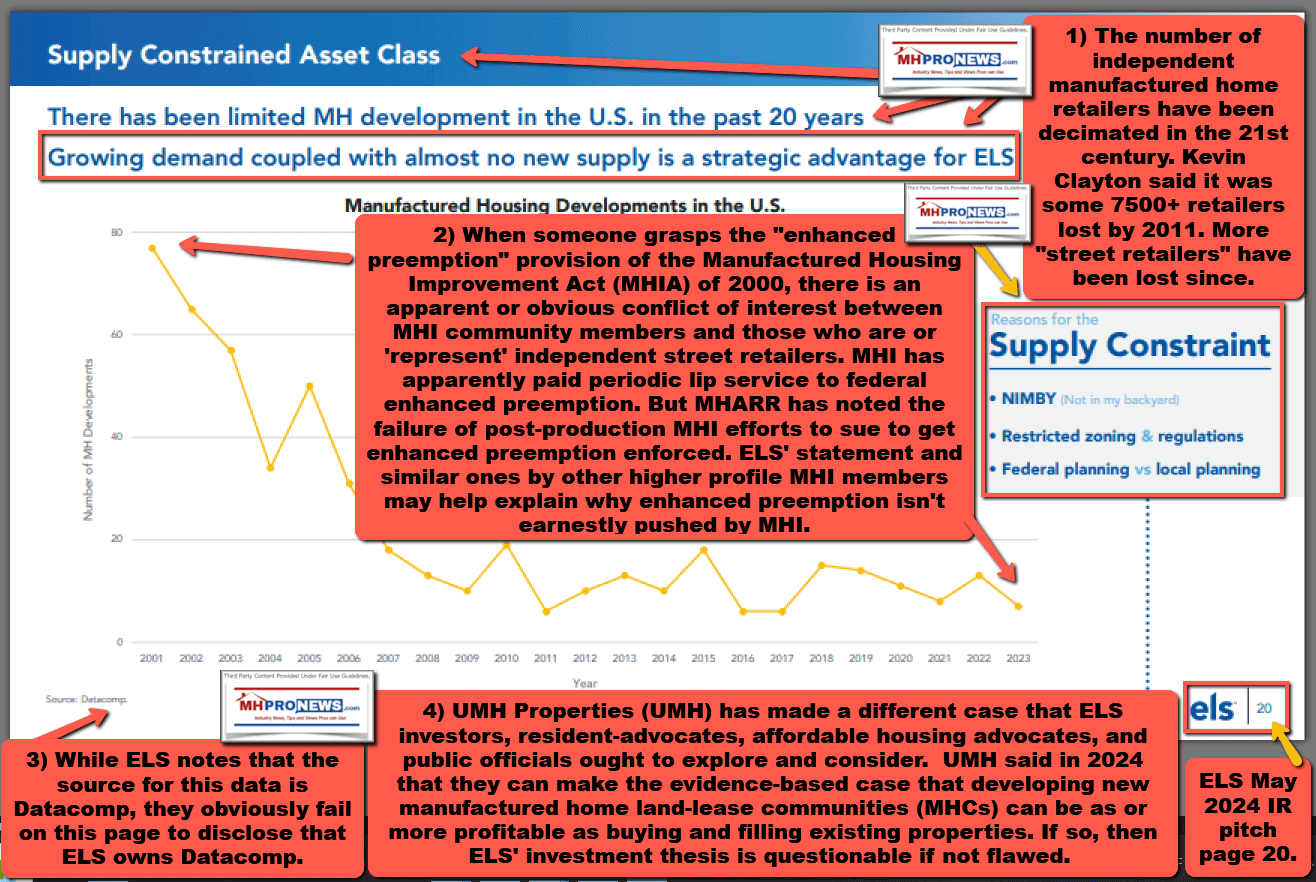

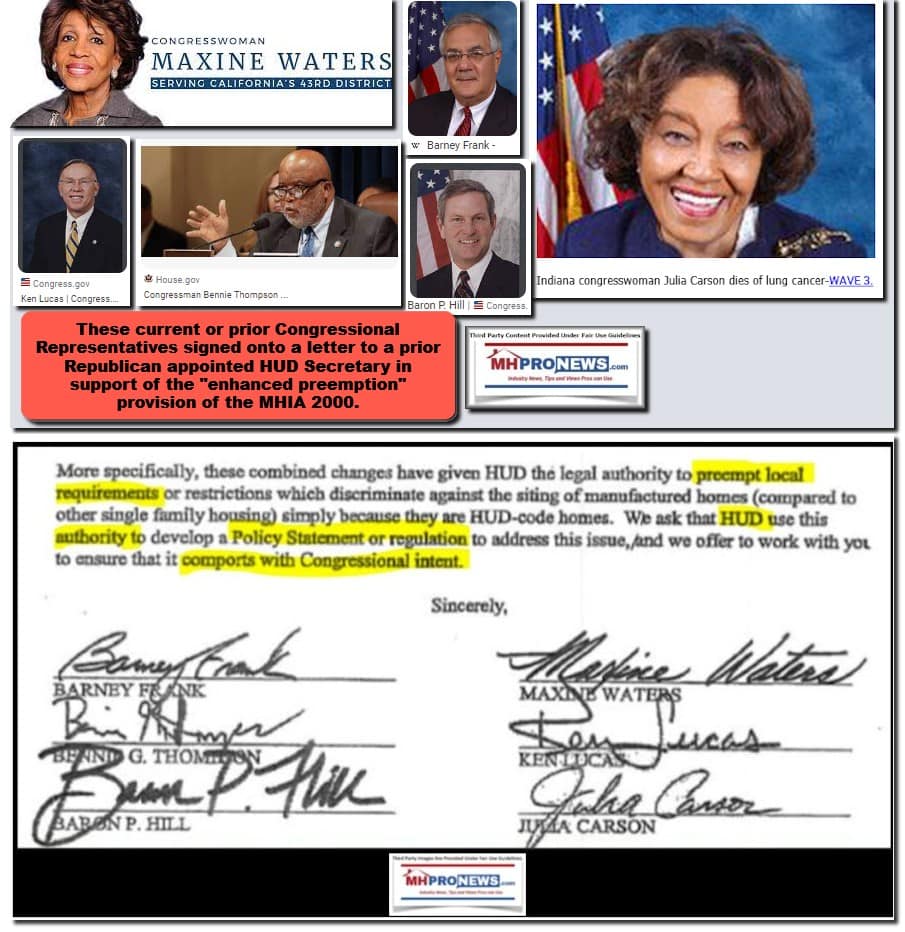

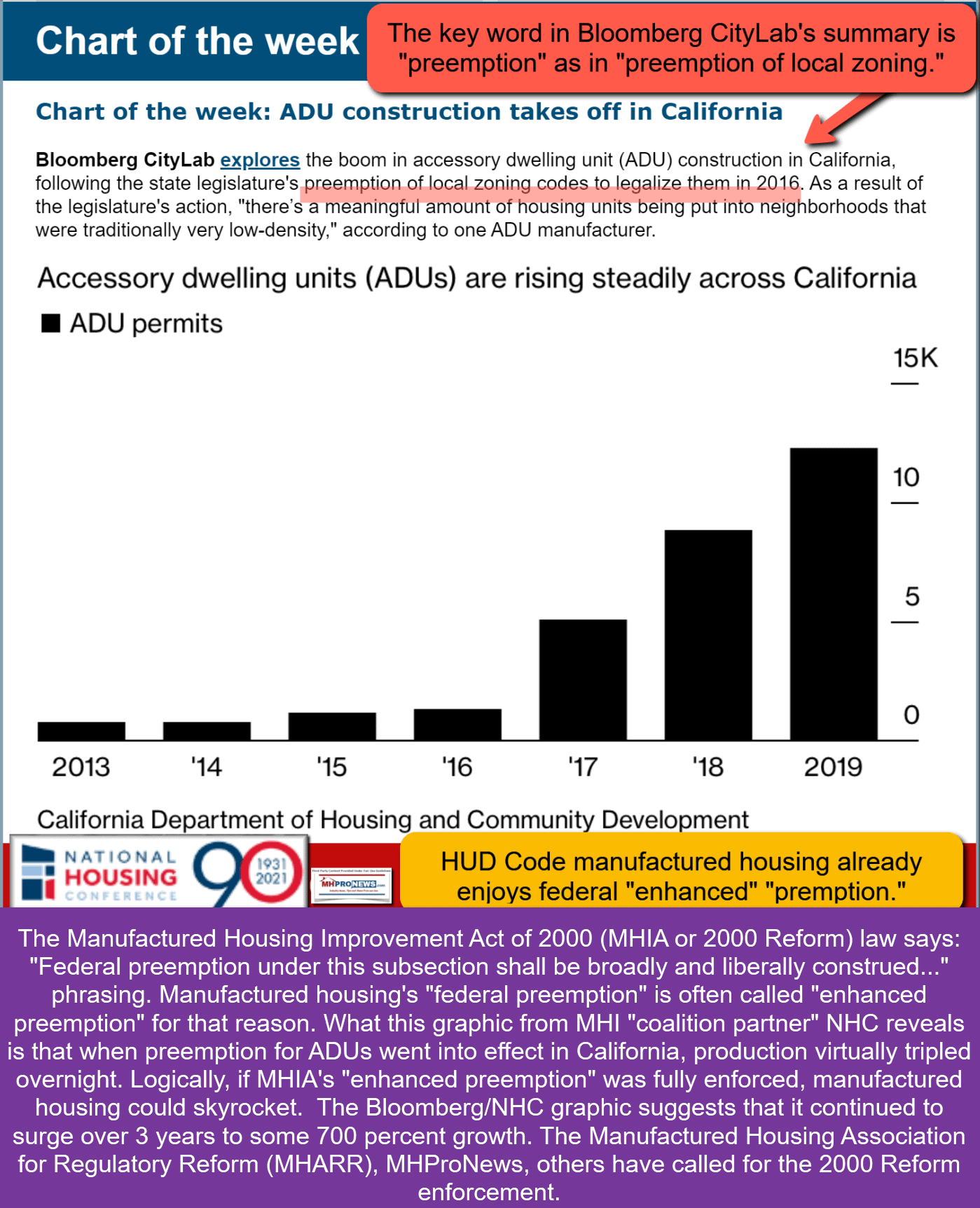

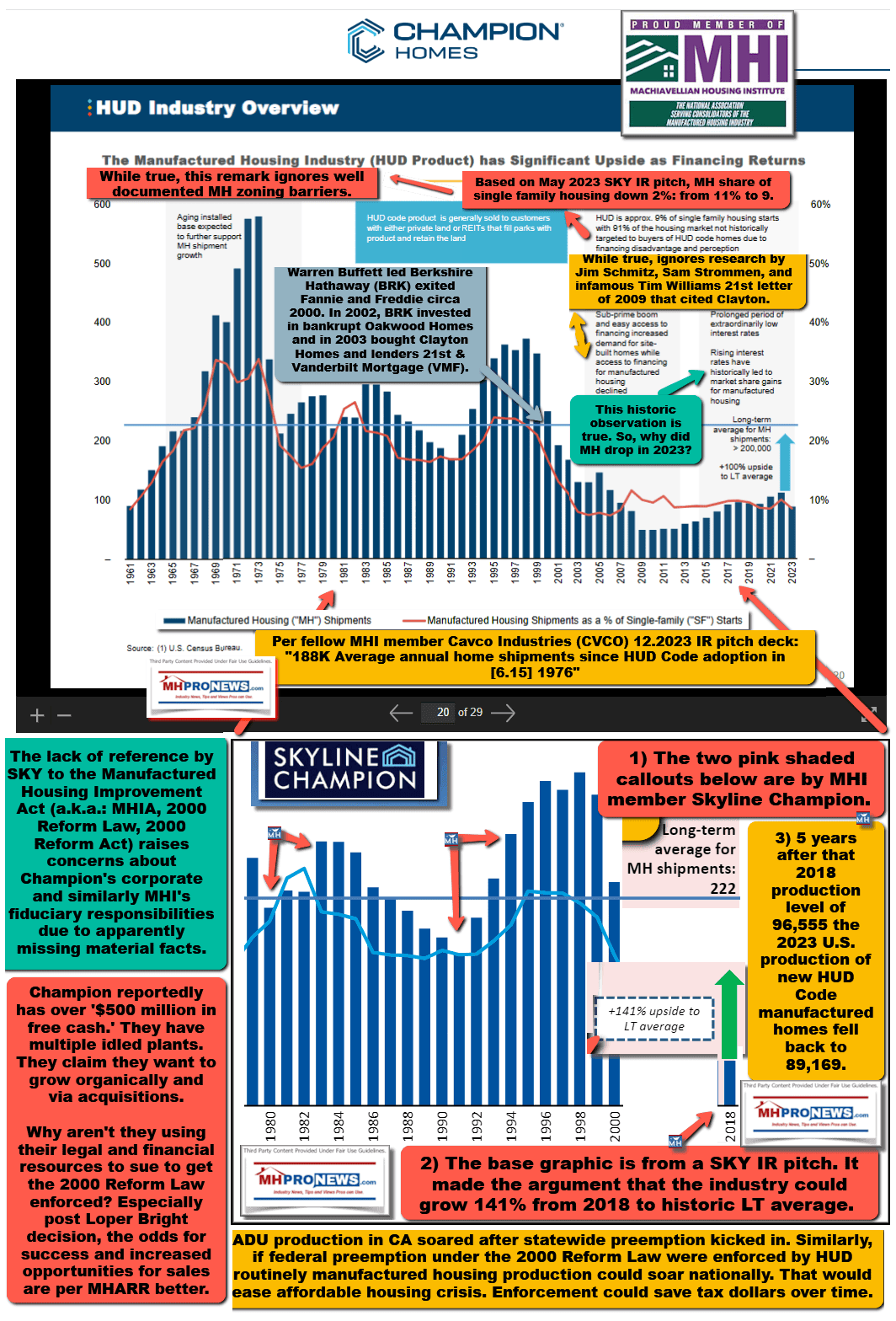

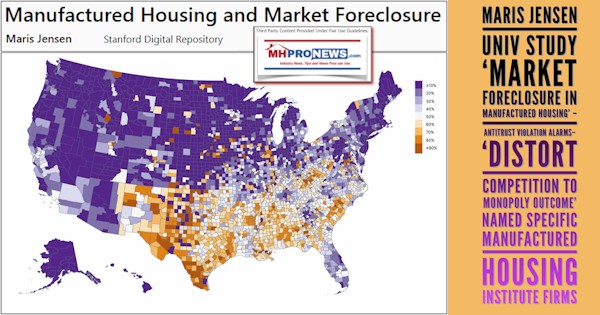

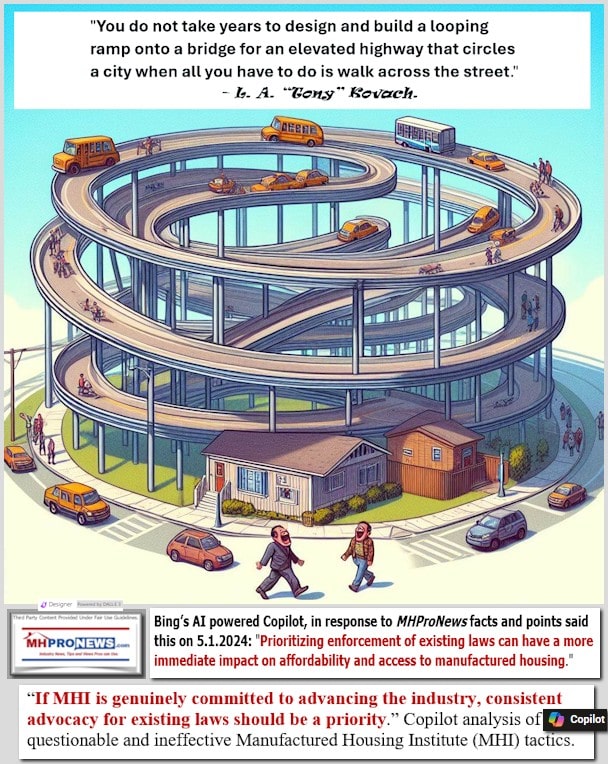

Federal preemption is a key issue for unlocking more HUD Code manufactured home production. “Look, the biggest headwind of this – in this entire industry is where to put these [HUD Code manufactured] homes.” So said Duncan Bates, President and CEO Legacy Housing (LEGH). Thus, the relevance and importance of this topic and article. Zoning and financing are the “bottlenecks” that are “holding back” manufactured housing production from surging back to levels not seen since the mid-to-late 1990s. That said, much of what follows in Part I is in one narrow sense unnecessary in this respect. Federal preemption under the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (a.k.a.: MHIA, MHIA 2000, 2000 Reform Law, 2000 Reform Act) is “expressed” preemption rather than “implied” preemption. See the illustration and content provided by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) to MHProNews shown in Part I below that shows the distinction between expressed and implied preemption. What makes this topic “a key” that can “unlock” mo

Because of the language in the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act, it is ‘expressed’ preemption vs. “implied” preemption.

One of the pull quotes from the below: Similarly, some preemption clauses bar said this.

“State or . . . political subdivision thereof” from regulating a certain subject matter, while others by their terms preempt only “State” laws.

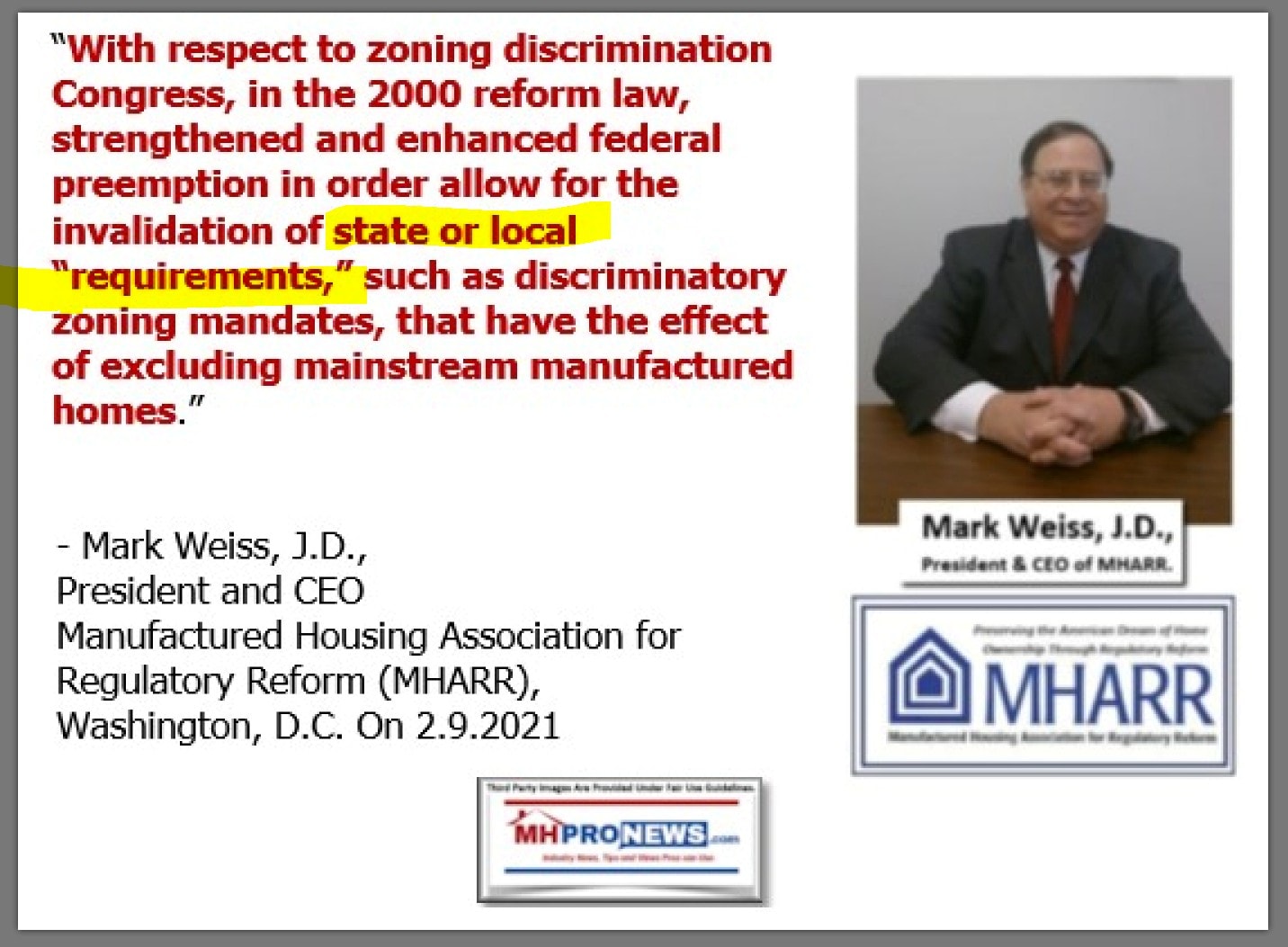

For the sake of the steady stream of newcomers to MHProNews, the President and CEO of the Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform (MHARR) is Mark Weiss, J.D. So, attorney wise, who has been deeply involved in the major laws impacting manufactured housing for decades, said the following in an article linked here.

Federal preemption can occur in one of two ways. A federal law, adopted by Congress, can specifically state that it – and valid enactments pursuant to its authority – preempt state and local enactments within the same field. This is referred-to as “express” preemption.

Weiss continued with these words.

Alternatively, federal preemption can be inferred by a court when a federal enactment conflicts with parallel state and/or local enactments. This is referred-to as “implied” or “conflict preemption.” In addition, preemption itself can be either complete or partial.

Jumping ahead, attorney Weiss wrote the following.

For manufactured housing, federal preemption is express, not implied, insofar as the law (in section 604(d)), expressly states that HUD enactments, pursuant to the Act’s authority, are preemptive. …

“Whenever a federal manufactured home construction and safety standard established under this title is in effect, no state or political subdivision of a state [i.e., locality] shall have authority either to establish or to continue in effect … any standard regarding construction or safety applicable to the same aspect of performance of such manufactured home which is not identical to the federal … standard.” (Emphasis added).

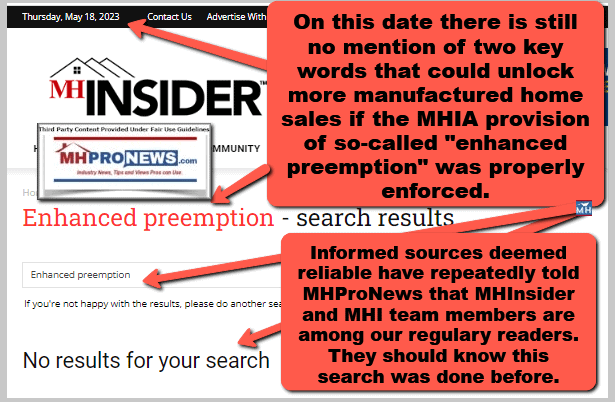

There is both useful and misleading information from a range of sources with respect to the preemption issue and how it relates to the manufactured housing industry.

According to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies 2024 research: “Restrictive Zoning and Land Use Regulation” is one of the top 5 issues facing the industry’s growth.

As the headline stated, what follows is from the Congression Research Service (CRS). While the CRS doesn’t specifically address the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act (a.k.a.: MHIA, MHIA 2000, 2000 Reform Act, 2000 Reform Law), the principles it is based upon are explained in this well-footnoted “legal primer” by attorneys Bryan L. Adkins, Alexander H. Pepper and Jay B. Sykes are useful.

While there are some familiar items to longtime readers of MHProNews, this article will provide an array of fresh insights in Part II after the information from CRS in Part I. More facts-evidence-analysis (FEA) and related will follow in Part II.

Part I – Congression Research Service report on Federal Preemption “A Legal Primer”

Federal Preemption: A Legal Primer

Updated May 18, 2023

Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45825

| Bryan L. Adkins

Legislative Attorney

Alexander H. Pepper Legislative Attorney

Jay B. Sykes Legislative Attorney |

Federal Preemption: A Legal Primer

The Constitution’s Supremacy Clause provides that federal law is “the supreme Law of the Land” notwithstanding any state law to the contrary. This language is the foundation for the doctrine of federal preemption, according to which federal law supersedes conflicting state laws. The Supreme Court has identified two general ways in which federal law can preempt state law. First, federal law can expressly preempt state law when a federal statute or regulation contains explicit preemptive language. Second, federal law can impliedly preempt state law when Congress’s preemptive intent is implicit in the relevant federal law’s structure and purpose.

In both express and implied preemption cases, the Supreme Court has made clear that Congress’s purpose is the “ultimate touchstone” of its statutory analysis. In analyzing congressional purpose, the Court has at times applied a canon of statutory construction known as the “presumption against preemption,” which instructs that federal law should not be read as superseding states’ historic police powers “unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress.”

In cases involving express preemption, the Supreme Court’s decisions have depended heavily on the details of particular statutory schemes, but the Court has assigned some phrases specific meanings even when they have appeared in different statutory contexts. The Court also must sometimes interpret savings clauses—statutory provisions designed to insulate certain categories of state law from federal preemption.

In implied preemption cases, the Court has identified two subcategories of implied preemption: field preemption and conflict preemption.

Field preemption occurs when a pervasive scheme of federal regulation implicitly precludes supplementary state regulation or when states attempt to regulate a field where there is a sufficiently dominant federal interest. Applying these principles, the Court has held that federal law occupies a number of regulatory fields, including alien registration, nuclear safety regulation, and the regulation of locomotive equipment.

Conflict preemption, in contrast, occurs when simultaneous compliance with both federal and state regulations is impossible (impossibility preemption) or when state law poses an obstacle to the accomplishment of federal goals (obstacle preemption).

The Court’s cases recognizing impossibility preemption are not limited to instances in which compliance with federal and state law is impossible in a literal sense. Rather, the Court has held that compliance with both federal and state law can be “impossible” even when a regulated party can petition the federal government for permission to comply with state law or avoid violations of the law by refraining from selling a regulated product altogether.

In its obstacle preemption decisions, the Court has concluded that state law can interfere with federal goals by frustrating Congress’s intent to adopt a uniform system of federal regulation; conflicting with Congress’s goal of establishing a regulatory ceiling for certain products or activities; or by impeding the vindication of a federal right.

Contents

General Preemption Principles…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3

The Primacy of Congressional Intent……………………………………………………………………………….. 3

The Presumption Against Preemption………………………………………………………………………………. 4

Language Commonly Used in Express Preemption Clauses……………………………………………………….. 6

“Related to”……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6

Employee Retirement Income Security Act………………………………………………………………….. 7

Airline Deregulation Act………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8

Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act………………………………………………………… 9

Takeaways………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10

“Covering”………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11

“In addition to, or different than”…………………………………………………………………………………… 11

“Requirements,” “Laws,” “Regulations,” and “Standards”………………………………………………….. 12

Savings Clauses……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13

Anti-Preemption Provisions…………………………………………………………………………………………. 14

Compliance Savings Clauses………………………………………………………………………………………… 15

Remedies Savings Clauses…………………………………………………………………………………………… 16

“State” vs. “State or Political Subdivision Thereof”…………………………………………………………… 16

Implied Preemption…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 17

Field Preemption……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 18

Examples……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 18

Takeaways………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 22

Conflict Preemption…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 23

Impossibility Preemption……………………………………………………………………………………….. 24

Obstacle Preemption……………………………………………………………………………………………… 25

Takeaways………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 28

Figures

Figure 1. Preemption Taxonomy ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3

Contacts

Author Information ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 29

MHProNews notes: the summary below is from the CRS download here and is from the CRS page found at this link here. This information has been ‘cut and pasted’ into the MHProNews publishing software. If there are an errors, the original document linked here should be considered as the correct source to be relied upon.

The Constitution’s Supremacy Clause provides that “the Laws of the United States . . . shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”1 This language is the foundation for the doctrine of federal preemption, under which federal law supersedes conflicting state laws.2

Federal preemption of state law is a ubiquitous feature of the modern regulatory state and “almost certainly the most frequently used doctrine of constitutional law in practice.”3 Preemptive federal statutes shape the regulatory environment for most major industries, including drugs and medical devices, banking, air transportation, securities, automobile safety, and tobacco.4

As a result, disputes over preemption “rage in the courts, in Congress, before agencies, and in the world of scholarship.”5 These debates implicate many of the themes that recur throughout both the Supreme Court’s preemption case law and the federalism literature. Proponents of broad federal preemption often cite the benefits of uniform national regulations[1] and the concentration of expertise in federal agencies.[2] Opponents typically appeal to the importance of policy experimentation,[3] the greater democratic accountability that they believe accompanies state and local regulation,9 and the gap-filling role of state common law in deterring harmful conduct and compensating injured plaintiffs.[4]

In addition to these general normative disputes, preemption decisions also raise narrower interpretive issues.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the Supreme Court has identified two general types of preemption. First, federal law can expressly preempt state law when a federal statute or regulation contains explicit preemptive language. Second, federal law can impliedly preempt state law when its structure and purpose implicitly reflect Congress’s preemptive intent.[5]

The Court has identified two subcategories of implied preemption: field preemption and conflict preemption.

Field preemption occurs when a pervasive scheme of federal regulation implicitly precludes supplementary state regulation or when states attempt to regulate a field where the federal interest is sufficiently dominant.[6]

In contrast, conflict preemption occurs when compliance with both federal and state regulations is impossible (impossibility preemption)[7] or when state law poses an “obstacle” to the accomplishment of the “full purposes and objectives” of Congress (obstacle preemption).14

Figure 1. Preemption Taxonomy

While the Supreme Court has repeatedly distinguished these preemption categories, it has also explained that the presence of a preemption clause in a federal statute does not preclude the possibility of implied preemption.[8] Congress must therefore consider the possibility that courts may construe statutes as impliedly preempting certain categories of state law even if such laws do not fall within the explicit terms of a preemption clause.

This report provides a general overview of federal preemption to inform Congress as it crafts laws implicating overlapping federal and state interests. The report begins by reviewing two general principles that have shaped the Court’s preemption jurisprudence: the primacy of congressional intent and the presumption against preemption.

The report then examines how courts have interpreted certain language that is commonly used in preemption clauses. Next, the report reviews judicial interpretations of statutory savings clauses—provisions that insulate certain categories of state law from federal preemption. Finally, the report discusses the Court’s implied preemption case law by examining illustrative examples of its field preemption, impossibility preemption, and obstacle preemption decisions.

General Preemption Principles

The Primacy of Congressional Intent

The Supreme Court has explained that in determining whether—and to what extent—federal law preempts state law, the purpose of Congress is the “ultimate touchstone” of its statutory analysis.[9] The Court has further instructed that Congress’s intent is discerned “primarily” from a statute’s text.17 The Court has also noted, however, the importance of statutory structure and purpose in determining how Congress intended a federal regulatory scheme to interact with related state laws.18 Like many of its statutory interpretation cases, then, the Court’s preemption decisions often involve disputes over the appropriateness of consulting extratextual evidence to determine Congress’s intent.19

The Presumption Against Preemption

In evaluating congressional purpose, the Supreme Court has at times employed a canon of construction called the “presumption against preemption,” which instructs that federal law should not be read to preempt laws involving the states’ historic police powers20 “unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress.”21 The presumption is rooted in principles of federalism and respect for state sovereignty.[10] While the Court has described the presumption against preemption as one of the “cornerstones” of its preemption jurisprudence, it has invoked the presumption inconsistently.[11]

- (“Congress’ intent, of course, primarily is discerned from the language of the pre-emption statute and the statutory framework surrounding it. Also relevant, however, is the structure and purpose of the statute as a whole, as revealed not only in the text, but through the reviewing court’s reasoned understanding of the way in which Congress intended the statute and its surrounding regulatory scheme to affect business, consumers, and the law.”) (citations and internal quotation marks omitted).

- See, e.g., Wyeth, 555 U.S. at 583 (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment) (rejecting the Court’s obstacle preemption jurisprudence as “inconsistent with the Constitution,” while noting that the Court “routinely invalidates state laws based on perceived conflicts with broad federal policy objectives, legislative history, or generalized notions of congressional purposes that are not embodied within the text of federal law”). For further background on the legal debate over using legislative history and other extratextual evidence to interpret statutes, see CRS Report R45153, Statutory Interpretation: Theories, Tools, and Trends, by Valerie C. Brannon.

- The Supreme Court uses the term “police power” to refer to the states’ general power of governing, such as regulating to promote public health, safety, and welfare. See, e.g., Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519, 536 (2012) (“Our cases refer to this general power of governing, possessed by the States but not by the Federal Government, as the ‘police power.’”).

- Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U.S. 218, 230 (1947); see also, e.g., Wyeth, 555 U.S. at 565 (“[I]n all preemption cases, and particularly in those in which Congress has legislated . . . in a field which the States have traditionally occupied, . . . we start with the assumption that the historic police powers of the States were not to be superseded by the Federal Act unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress.’”) (citations and internal quotation marks omitted); N.Y. State Conf. of Blue Cross & Blue Shield Plans v. Travelers Ins. Co., 514 U.S. 645, 654 (1995) (“[W]e have never assumed lightly that Congress has derogated state regulation, but instead have addressed claims of pre-emption with the starting presumption that Congress does not intend to supplant state law.”); Puerto Rico Dep’t of Consumer Affs. v. Isla Petroleum Corp., 485 U.S. 495, 500 (1988) (“As we have repeatedly stated, we start with the assumption that the historic police powers of the States were not to be superseded by the Federal Act unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress.”) (citations and internal quotation marks omitted).

In a 2016 decision, the Court also appeared to depart from prior case law24 when it suggested that the presumption did not apply in express preemption cases.25 Since that decision, lower courts have disagreed over the presumption’s application to interpretations of preemption clauses.[12] Although several federal circuit courts have held that the presumption no longer applies in express preemption cases,[13] one circuit court has concluded that the presumption remains valid in cases involving areas historically regulated by states.[14]

The Supreme Court has also appeared to endorse a narrower exception to the presumption against preemption involving areas in which the federal government has traditionally had a “significant” regulatory presence.[15] In United States v. Locke, the Court held that the federal Ports and Waterways Safety Act preempted state regulations involving maritime commerce—an area in which there was a “history of significant federal presence.”[16] When a state regulates in such an area, the Court explained, “there is no beginning assumption that concurrent regulation by the State is a valid exercise of its police powers.”[17]

In a subsequent decision, however, the Court appeared to retreat from its reasoning in Locke. In its 2009 decision in Wyeth v. Levine, the Court invoked the presumption when it held that federal law did not preempt certain state law claims concerning drug labeling.[18] In allowing the claims to proceed, the Court acknowledged that the federal government had regulated drug labeling for more than a century, but explained that the presumption can apply even when the federal government has long regulated a subject.[19]

Whether the presumption continues to apply in fields traditionally regulated by the federal government thus remains unclear.

Language Commonly Used in Express Preemption Clauses

Congress often relies on the language of existing preemption clauses in drafting new legislation.34 This type of reliance can have important consequences, as courts often look to the settled meaning of statutory language to discern Congress’s intent.35

This section of the report discusses how the Supreme Court has interpreted federal statutes that expressly preempt (1) state laws “related to” certain subjects, (2) state laws concerning certain subjects “covered” by federal laws and regulations, (3) state requirements that are “in addition to, or different than” federal requirements, and (4) state “requirements,” “laws,” “regulations,” and “standards.”[20]

While preemption decisions depend heavily on the details of particular statutory schemes, the Court has assigned some of these phrases specific meanings even when they have appeared in different statutory contexts.

“Related to”

Some preemption clauses provide that a federal statute supersedes all state laws that are “related to” a specific matter of federal regulatory concern. The Supreme Court has characterized such provisions as “deliberatively expansive”[21] and “conspicuous for [their] breadth.”38

At the same time, the Court has cautioned against strictly literal interpretations of “related to” preemption clauses. Instead of reading such clauses “to the furthest stretch of [their] indeterminacy,”39 the Court has looked to Congress’s statutory objectives to cabin the clauses’ scope.40

The following subsections discuss the Court’s interpretation of three statutes that contain “related to” preemption clauses: the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, the Airline Deregulation Act, and the Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act.

Employee Retirement Income Security Act

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) contains perhaps the most prominent example of a preemption clause that uses “related to” language.[22] ERISA imposes comprehensive federal regulations on private employee benefit plans.42 The statute also contains a preemption clause providing that its requirements preempt all state laws that “relate to” regulated benefit plans.43

In interpreting this provision, the Supreme Court has held that ERISA preempts two categories of state law: (1) state laws that have a “connection with” ERISA plans, and (2) state laws that contain a “reference to” ERISA plans.[23]

The Court has held that state laws have an impermissible “connection with” ERISA plans if they govern “a central matter of plan administration” or interfere with “nationally uniform plan administration.”[24] In contrast, state laws that indirectly affect ERISA plans are not preempted unless the relevant effects are particularly “acute.”[25]

Applying these standards, the Court has ruled that ERISA preempts state laws governing areas of “core ERISA concern,” like the designation of ERISA plan beneficiaries[26] and the disclosure of information regarding health plan benefits.[27]

In contrast, the Supreme Court has held that ERISA does not preempt state laws imposing surcharges on certain types of insurers[28] and mandating wage levels for specific categories of employees who work on public projects.[29] The Court has explained that these state laws are permissible because they affect ERISA plans only indirectly and that ERISA preempts such laws only if the relevant indirect effects are particularly strong.[30][31]

The Court has also held that ERISA preempts state laws that contain an impermissible “reference to” ERISA plans. Under the Court’s case law, a state law will contain an impermissible “reference to” ERISA plans where it “acts immediately and exclusively upon ERISA plans,” or where the existence of an ERISA plan is “essential” to the state law’s operation.52

In Mackey v. Lanier Collection Agency & Service, Inc., for example, the Supreme Court concluded that ERISA preempted a state statute that prohibited the garnishment of funds in plans “subject to . . . [ERISA].”53 Because the challenged state statute expressly referenced ERISA plans, the Court held that it fell within the scope of ERISA’s preemption clause even if it was enacted “to help effectuate ERISA’s underlying purposes.”[32][33]

Similarly, in Ingersoll-Rand Company v. McClendon, the Court held that ERISA preempted an employee’s state law claim alleging that he was terminated in order to prevent his regulated pension from vesting.55 The Court reasoned that ERISA preempted this state law claim because the action made specific reference to and was premised on the existence of an ERISA-regulated pension plan.[34][35]

The Supreme Court’s decision in District of Columbia v. Greater Washington Board of Trade offers a third example of preemption based on a state law’s “reference to” ERISA plans.57 There, the Court held that ERISA preempted a state statute requiring employers that provided health insurance to their employees to continue providing coverage at existing benefit levels while employees received workers’ compensation benefits.[36] This state law was preempted, the Court concluded, because ERISA regulates employee health insurance, meaning that the state law specifically referred to ERISA-regulated plans.[37][38]

Airline Deregulation Act

The Airline Deregulation Act (ADA) is another example of a statute that employs “related to” preemption language.60 Enacted in 1978, the ADA largely deregulated domestic air transportation.[39][40]

To ensure that state governments did not interfere with this deregulatory effort, the ADA prohibits states from enacting laws “related to a price, route, or service of an air carrier.”62

In interpreting this language, the Supreme Court has relied upon similar reasoning as used in its

ERISA decisions, concluding that the ADA preempts state laws that have a “connection with” or “reference to” airline prices, routes, or services.[41]

In Morales v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., for example, the Court relied in part on its ERISA case law to hold that the ADA preempted a state’s effort to enforce guidelines regarding the content and format of airline fare advertising.[42] The Court reached this conclusion on the grounds that the guidelines expressly referenced airfares and were likely to have a significant impact on airfares.[43][44]

Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act

The Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act of 1994 (FAAA) is a third example of a statute that utilizes “related to” preemption language.66 While the FAAA is (as its title suggests) principally concerned with aviation regulation, it also supplemented Congress’s deregulation of the trucking industry. The statute pursued this objective with a preemption clause prohibiting states from enacting laws “related to a price, route, or service of any motor carrier . . . with respect to the transportation of property.”[45][46]

In Rowe v. New Hampshire Motor Transport Association, the Supreme Court relied in part on its ERISA and ADA case law to hold that the FAAA preempted certain state laws regulating the delivery of tobacco, including a law that required retailers shipping tobacco to employ motor carriers that utilized certain kinds of recipient-verification services.68

The Court reached this conclusion for two principal reasons. First, the Court reasoned that the requirement had an impermissible “connection with” motor carrier services because it “focuse[d] on” such services.[47] Second, the Court concluded that the FAAA preempted the state law because of the state law’s significant adverse effects on the federal statute’s deregulatory objectives. Specifically, the Court reasoned that the state law had a “connection with” these objectives because it dictated that motor carriers use certain types of recipient-verification services, thereby substituting the state’s commands for competitive market forces.[48][49]

Although the Supreme Court has thus relied on its ERISA and ADA case law in interpreting the FAAA’s preemption clause, the Court has also explained that the clause’s “with respect to” qualifying language significantly narrows the statute’s preemptive scope.

In Dan’s City Used Cars, Inc. v. Pelkey, the Court relied on this language to hold that the FAAA did not preempt state law claims involving the storage and disposal of a towed car.71 In allowing the claims to proceed, the Court observed that the FAAA’s preemption clause mirrored the ADA’s preemption clause with “one conspicuous alteration”—the addition of the phrase “with respect to the transportation of property.”[50] According to the Court, this phrase “massively” limited the scope of FAAA preemption.[51] Because the relevant state law claims involved the storage and disposal of towed vehicles rather than their transportation, the Court held that they did not qualify as state laws that “related to” motor carrier services “with respect to the transportation of property.”74

Takeaways

The Supreme Court’s case law concerning “related to” preemption clauses reflects a number of general principles. The Court has consistently held that state laws “relate to” matters of federal regulatory concern when they have a “connection with” or contain a “reference to” such matters.[52]

Generally, state laws have an impermissible “connection with” matters of federal concern when they:

- prescribe rules governing an issue central to the relevant federal regulatory scheme;[53]

- interfere with uniform national policies regarding a matter of federal concern;[54] or

- have indirect effects on the federal scheme that are particularly “acute”[55] or “significant.”[56]

As a corollary to the latter principle, the Court has made clear that state laws having only “tenuous, remote, or peripheral” effects on an issue of federal concern are not sufficiently “related to” the issue to warrant preemption.[57]

The Court has concluded that state laws contain a “reference to” a matter of federal regulatory interest if they “act[] immediately and exclusively upon” the matter or if the existence of a federal regulatory scheme is “essential” to the state law’s operation.[58]

The inclusion of qualifying language can narrow the scope of “related to” preemption clauses. As the Court made clear in Dan’s City, the scope of “related to” preemption clauses can be significantly limited by the addition of “with respect to” qualifying language.82

“Covering”

The Federal Railroad Safety Act contains a preemption clause allowing states to regulate railroad safety until the federal government prescribes a regulation or issues an order “covering the subject matter” of the relevant state requirement.83

In CSX Transportation, Inc. v. Easterwood, the Supreme Court interpreted this language as having a narrower effect than “related to” preemption clauses.84 The Court explained that “covering” is a more restrictive term than “related to,” and that federal law will accordingly cover the subject of a state law only if it “substantially subsume[s]” that subject.85

Applying this standard, the Court held that federal regulations of grade crossing safety did not preempt state law claims alleging that a train operator failed to maintain adequate warning devices at a crossing where a collision had occurred.[59] The Court allowed these claims to proceed because the relevant federal regulations did not “substantially subsume” the subject of warning device adequacy.[60]

At the same time, the Easterwood Court held that federal regulations preempted other state law claims alleging that a train traveled at an unsafe speed. In holding that these claims were preempted, the Court reasoned that federal maximum-speed regulations “substantially subsumed”—and therefore “covered”—the subject of train speeds.88

“In addition to, or different than”

A number of federal statutes preempt state requirements that are “in addition to, or different than” federal requirements.[61] The Supreme Court has explained that these statutes preempt state law even in cases where a regulated entity can comply with both federal and state requirements.

The Court adopted this position in National Meat Association v. Harris, where it interpreted a preemption clause in the Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA) prohibiting states from imposing requirements on meatpackers and slaughterhouses that are “[62]in addition to, or different than” federal requirements.90

In Harris, the Court held that certain California slaughterhouse regulations were “in addition to, or different than” federal regulations because they imposed a distinct set of requirements that went beyond those imposed by federal law.[63] Because the California requirements differed from federal requirements, the Court explained, they fell within the plain meaning of the FMIA’s preemption clause, even though slaughterhouses were able to comply with both sets of restrictions.[64]

Preemption clauses that employ “in addition to, or different than” language often raise a second interpretive issue involving the status of state requirements that are identical to federal requirements.

The Supreme Court has interpreted two statutes employing this language to not preempt parallel state law requirements.[65] In instructing lower courts on how to assess whether state requirements in fact parallel federal requirements, the Court has explained that state law need not explicitly incorporate federal standards in order to avoid qualifying as “in addition to, or different than” federal requirements.[66] Instead, the relevant inquiry looks to the substance of state requirements to determine whether they mirror federal law.

The Court has also explained that state requirements do not qualify as “in addition to, or different than” federal requirements simply because state law provides injured plaintiffs with different remedies than federal law.[67] Accordingly, absent contextual evidence to the contrary, preemption clauses that employ “in addition to, or different than” language will allow states to give plaintiffs a damages remedy for violations of state requirements even where federal law does not offer such a remedy for violations of parallel federal requirements.96

“Requirements,” “Laws,” “Regulations,” and “Standards”

Federal statutes frequently preempt state “requirements,” “laws,” “regulations,” and/or “standards” concerning subjects of federal regulatory concern.[68] These preemption clauses have raised the question of whether they encompass state common law actions.

The Supreme Court has explained that, absent evidence to the contrary, a preemption clause’s reference to state “requirements” includes state common law duties.[69]

In contrast, the Court has interpreted one preemption clause’s reference to state “law[s] or regulation[s]” as encompassing only “positive enactments” and not common law actions.[70] The Court reached this conclusion in Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine, where it held that the Federal Boat

Safety Act of 1971 (FBSA) did not preempt common law claims involving boat safety.[71][72] The FBSA contains a preemption clause prohibiting states from enforcing “a law or regulation” concerning boat safety that is not identical to federal laws and regulations.101 The statute also includes a savings clause providing that compliance with federal requirements does not “relieve a person from liability at common law or under State law.”[73]

In Sprietsma, the Court held that the phrase “law or regulation” in the FBSA’s preemption clause did not encompass state common law claims for three reasons.[74] First, the Court reasoned that the inclusion of the article “a” before “law or regulation” implied a “discreteness” that is reflected in statutes and regulations, but not in common law.[75] Second, the Court concluded that the pairing of the terms “law” and “regulation” indicated that Congress intended to preempt only positive enactments. In particular, the Court reasoned that if the term “law” were given an expansive interpretation that included common law claims, it would also encompass “regulations” and thereby render the inclusion of that latter term superfluous.[76] Third, the Court reasoned that the FBSA’s savings clause provided additional support for the conclusion that the phrase “law or regulation” did not encompass common law actions.[77]

With respect to federal statutes that preempt state “standards,” the Supreme Court has explained that it is possible to interpret “standards” as encompassing common law actions, but it has interpreted the term more narrowly where the specific statutory context suggested that Congress did not intend to preempt common-law tort actions.[78]

Savings Clauses

Many federal statutes contain provisions that purport to restrict their preemptive effect. These savings clauses make clear that federal law does not preempt certain categories of state law, reflecting Congress’s recognition of the need for states to “fill a regulatory void” or “enhance protection for affected communities” through supplementary regulation.[79]

The law regarding savings clauses “is not especially well developed,” and cases involving such clauses “turn very much on the precise wording of the statutes at issue.”109

With these caveats in mind, this section discusses three general categories of savings clauses: (1) “anti-preemption provisions,” (2) “compliance savings clauses,” and (3) “remedies savings clauses.”

Anti-Preemption Provisions

Some savings clauses contain language indicating that “nothing in” the relevant federal statute “may be construed to preempt or supersede” certain categories of state law.110 Others say that the relevant federal statute “does not annul, alter, or affect” state laws “except to the extent that those laws are inconsistent” with the federal statute.111 Certain statutes containing this “inconsistency” language further provide that state laws are not “inconsistent” with the relevant federal statute if they provide greater protection to consumers than federal law.112 Some courts and commentators have labeled these clauses “anti-preemption provisions.”113

Courts have given effect to the plain language of these provisions, concluding that they evince

Congress’s intent to allow states to adopt regulations that are consistent with federal law.114

- UNTEREINER, supra note 34, at 204–05.

- See, e.g., 7 U.S.C. 2910(a) (“Nothing in this chapter may be construed to preempt or supersede any other program relating to beef promotion organized and operated under the laws of the United States or any State.”); id. § 6812(c) (“Nothing in this chapter may be construed to preempt or supersede any other program relating to cut flowers or cut greens promotion and consumer information organized and operated under the laws of the United States or a State.”); id. § 7811(c) (“Nothing in this chapter may be construed to preempt or supersede any other program relating to Hass avocado promotion, research, industry information, and consumer information organized and operated under the laws of the United States or of a State.”).

- See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. 2616 (“This chapter does not annul, alter, or affect, or exempt any person subject to the provisions of this chapter from complying with, the laws of any State with respect to [real estate] settlement practices, except to the extent that those laws are inconsistent with any provision of this chapter, and then only to the extent of the inconsistency.”); 15 U.S.C. § 1693q (“This subchapter does not annul, alter, or affect the laws of any State relating to electronic fund transfers, dormancy fees, inactivity charges or fees, service fees, or expiration dates of gift certificates, store gift cards, or general-use prepaid cards, except to the extent that those laws are inconsistent with the provisions of this subchapter, and then only to the extent of the inconsistency.”); 15 U.S.C. § 5722(a) (“This subchapter does not annul, alter, or affect, or exempt any person subject to the provisions of this subchapter from complying with, the laws of any State with respect to telephone billing practices, except to the extent that those laws are inconsistent with any provision of this subchapter, and then only to the extent of the inconsistency.”).

- 12 U.S.C. 2616 (authorizing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to determine whether state laws are “inconsistent with” the relevant federal statute, and providing that the CFPB “may not determine that any State law is inconsistent with” the federal statute “if the [CFPB] determines that such law gives greater protection to the consumer.”); 15 U.S.C. § 1693q (“A State law is not inconsistent with this subchapter if the protection such law affords any consumer is greater than the protection afforded by this subchapter.”); 15 U.S.C. § 5722(a) (authorizing the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to determine whether state laws are “inconsistent with” the relevant federal statute, and providing that the FTC “may not determine that any State law is inconsistent with” the federal statute “if the [FTC] determines that such law gives greater protection to the consumer.”).

- See Gobeille v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 577 U.S. 312, 326 (2016); Bank of Am. v. City & Cnty. of S.F., 309 F.3d 551, 565 (9th Cir. 2002); Bank One v. Guttau, 190 F.3d 844, 850 (8th Cir. 1999); UNTEREINER, supra note 34, at 20. 114 See, e.g., Perkins v. Johnson, 551 F. Supp. 2d 1246, 1255 (D. Colo. 2008).

Compliance Savings Clauses

Some savings clauses provide that compliance with federal law does not relieve a person from liability under state law.115 The principal interpretive issue with such clauses is whether they limit a statute’s preemptive effect (a question of federal law) or are instead intended to discourage the conclusion that compliance with federal regulations necessarily renders a product nondefective as a matter of state tort law.116

While the Supreme Court has not adopted a generally applicable rule concerning the meaning of compliance savings clauses, it has concluded that such clauses can support a narrow interpretation of a statute’s preemptive effect.

In Geier v. American Honda Motor Co., the Court relied in part on a compliance savings clause in the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act (NTMVSA) to hold that the statute did not expressly preempt state common law claims against an automobile manufacturer.117 The NTMVSA contains a preemption clause prohibiting states from enforcing safety standards for motor vehicles that are not identical to federal standards.118 The statute also includes a savings clause providing that compliance with federal safety standards does not “exempt any person from any liability under common law.”119

In Geier, the Court explained that, although it was “possible” to read the NTMVSA’s preemption clause standing alone as encompassing the state law claims, that reading of the statute would leave the Act’s savings clause without effect.120 The Court thus held that the NTMVSA did not expressly preempt state common law claims based in part on the Act’s savings clause.121

Similarly, as discussed, the Court’s decision in Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine indicated that a compliance savings clause in the FBSA “buttresse[d]” the conclusion that state common law claims did not qualify as “law[s] or regulation[s]” within the meaning of the statute’s preemption clause.122

The Court has thus relied on compliance savings clauses to inform its interpretation of preemption clauses, but has not held that such clauses automatically insulate state laws from preemption.

Remedies Savings Clauses

Some savings clauses provide that “nothing in” a federal statute “shall in any way abridge or alter the remedies now existing at common law or by statute.”123 While the case law on these “remedies savings clauses” is limited, the Supreme Court has interpreted one such clause as evincing Congress’s intent to disavow field preemption, but not as preserving state laws that conflict with federal objectives.124

“State” vs. “State or Political Subdivision Thereof”

Some savings clauses limit a federal statute’s preemptive effect with respect to certain laws enacted by “State[s] or political subdivisions thereof,”125 while others by their terms insulate only “State” laws.[80]

- 47 U.S.C. 414. See also 7 U.S.C. § 209(b) (“[T]his section shall not in any way abridge or alter the remedies now existing at common law or by statute, but the provisions of this chapter are in addition to such remedies.”); id. § 499e(b) (“[T]his section shall not in any way abridge or alter the remedies now existing at common law or by statute, and the provisions of this chapter are in addition to such remedies.”).

- See Pennsylvania R.R. v. Puritan Coal Mining Co., 237 U.S. 121, 129–30 (1915) (“The [savings clause] was added . . . not to nullify other parts of the act, or to defeat rights or remedies given by preceding sections, but to preserve all existing rights which were not inconsistent with those created by the statute . . . But for this proviso . . . , it might have been claimed that, Congress having entered the field, the whole subject of liability of carrier to shippers in interstate commerce had been withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the state courts, and this clause was added to indicate that the commerce act, in giving rights of action in Federal courts, was not intended to deprive the state courts of their general and concurrent jurisdiction.”); see also Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Cent. Off. Tel., Inc., 524 U.S. 214, 226 (1998) (holding that a remedies savings clause in the Communications Act of 1934 did not save state laws that were inconsistent with federal law).

- See, e.g., 33 U.S.C. 1370 (“[N]othing in this chapter shall . . . preclude or deny the right of any State or political subdivision thereof . . . to adopt or enforce . . . any standard or limitation respecting discharges of pollutants. . . .”) (emphasis added); 42 U.S.C. § 2018 (“Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to affect the authority or regulations of any Federal, State, or local agency with respect to the generation, sale, or transmission of electric power produced through the use of nuclear facilities licensed by the Commission.”) (emphasis added); 42 U.S.C. § 6929 (“Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to prohibit any State or political subdivision thereof from imposing any requirements, including those for site selection, which are more stringent than those imposed by such regulations.”) (emphasis added).

The Supreme Court has [81]twice held that savings clauses that by their terms applied only to “State” laws also insulated local laws from preemption.

In Wisconsin Public Intervenor v. Mortier, the Court held that the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act did not preempt local ordinances regulating pesticides based in part on a savings clause providing that “State[s]” may regulate federally registered pesticides in certain circumstances.127 In concluding that the term “State” included political subdivisions of states, the Court relied on the principle that local governments are “convenient agencies” by which state governments can exercise their powers.[82][83]

Similarly, in City of Columbus v. Ours Garage & Wrecker Service, Inc., the Court held that the Interstate Commerce Act (ICA) did not preempt municipal safety regulations governing tow-truck operators based in part on a savings clause providing that the ICA “shall not restrict the safety regulatory authority of a State with respect to motor vehicles.”129 Relying in part on its reasoning in Mortier, the Court explained that, absent a clear statement to the contrary, Congress’s reference to the regulatory authority of a “State” should be read to preserve “the traditional prerogative of the States to delegate their authority to their constituent parts.”[84]

Implied Preemption

As discussed, federal law can impliedly preempt state law even when it does not do so expressly.[85] Like its express preemption decisions, the Supreme Court’s implied preemption cases focus on Congress’s intent.[86]

The Supreme Court has recognized two general forms of implied preemption: field preemption and conflict preemption. Field preemption occurs when a pervasive scheme of federal regulation implicitly precludes supplementary state regulation or when states attempt to regulate a field where there is a sufficiently dominant federal interest.[87] Conflict preemption occurs when state law interferes with federal goals.[88]

U.S.C. § 360eee-4(b)(2) (“No State shall regulate third-party logistics providers as wholesale distributors.”) (emphasis added); 42 U.S.C. § 7543(a) (“No State shall require certification, inspection, or any other approval relating to the control of emissions from any new motor vehicle or new motor vehicle engine as condition precedent to the initial retail sale, titling (if any), or registration of such motor vehicle, motor vehicle engine, or equipment.”) (emphasis added).

Field Preemption

The Supreme Court has held that federal law preempts state law where Congress has manifested an intention that the federal government occupy an entire field of regulation.[89] Federal law may reflect such an intent through a scheme of federal regulation that is “so pervasive as to make reasonable the inference that Congress left no room for States to supplement it,” or where federal law concerns “a field in which the federal interest is so dominant that the federal system will be assumed to preclude enforcement of state laws on the same subject.”[90]

Applying these principles, the Court has held that federal law occupies a variety of regulatory fields, including alien registration;[91] nuclear safety;[92] aircraft noise;[93] the “design, construction, alteration, repair, maintenance, operation, equipping, personnel qualification, and manning” of tanker vessels;[94] wholesales of natural gas in interstate commerce;[95] and locomotive equipment.[96][97]

Examples

Grain Warehousing

In its 1947 decision in Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., the Supreme Court held that federal law preempted a number of fields related to grain warehousing, precluding even complementary state regulations of those fields.143 In that case, the Court held that the federal Warehouse Act and associated regulations preempted a variety of state law claims brought against a grain warehouse, including allegations that the warehouse had engaged in unfair pricing, maintained unsafe elevators, and impermissibly mixed different qualities of grain.[98]

The Court discerned Congress’s intent to occupy the relevant fields from an amendment to the Warehouse Act that made the Secretary of Agriculture’s authorities “exclusive” vis-à-vis federally licensed warehouses.145 Because the text and legislative history of this amendment reflected Congress’s intent to eliminate overlapping federal and state warehouse regulations, the Court held that federal law occupied a number of fields involving grain warehousing. As a result, the Court concluded that the Warehouse Act preempted certain state law claims that intruded into those federally regulated fields, even if federal law established standards that were less strict than those imposed by state law.146

Immigration: Alien Registration

The Court has also held that federal law preempts the field of alien registration.147 In its 1941 decision in Hines v. Davidowitz, the Court held that federal immigration law—which required aliens to register with the federal government—preempted a Pennsylvania law that required aliens to register with the state, pay a registration fee, and carry an identification card.148 The Court explained that alien regulation is “intimately blended and intertwined” with the federal government’s core responsibilities and that Congress had enacted a “complete” regulatory scheme involving that field, meaning federal law preempted the additional state requirements.[99]

The Court reaffirmed these general principles in its 2012 decision in Arizona v. United States.[100] In Arizona, the Court held that the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which requires aliens to carry an alien registration document,151 preempted an Arizona statute that made violations of that federal requirement a crime under state law.[101]

In holding that federal law preempted this Arizona requirement, the Court explained that—like the statutory framework at issue in Hines—the INA represented a “comprehensive” regulatory regime that occupied the field of alien registration.[102] The Court inferred Congress’s intent to occupy this field from the INA’s “full set of standards” governing alien registration, which included specific penalties for noncompliance.154 The Court thus held that federal law preempted even complementary state laws regulating alien registration, like the challenged Arizona requirement.[103]

The Court has also made clear, however, that other types of state laws concerning aliens do not necessarily fall within the preempted field of alien registration. In its 1976 decision in De Canas the [104]employment of aliens not entitled to lawful residence in the United States.156 The Court based this conclusion on the absence of provisions regulating employment eligibility in the INA at the time.[105][106]

The Court has also upheld several state laws regulating the activities of aliens since De Canas. In Chamber of Commerce v. Whiting, for example, the Court held that federal law did not preempt an Arizona statute allowing the state to revoke an employer’s business license for hiring aliens who did not possess work authorization.158

Nuclear Energy: Safety Regulation

The Supreme Court has also held that federal law preempts the field of nuclear safety regulation. The Court has explained, however, that this field does not encompass all state laws that affect safety decisions made by nuclear power plants. Instead, the Court has concluded that state laws fall within the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation if they (1) are motivated by safety concerns and implicate a “core federal power,” or (2) have a “direct and substantial” effect on safety decisions made by nuclear facilities.[107]

This division of authority is the result of a regulatory regime that has changed significantly over the course of the 20th century. The federal government initially maintained a monopoly over the use, control, and ownership of nuclear technology.[108] Beginning in 1954, however, the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) allowed private entities to own, construct, and operate nuclear power plants subject to a “strict” licensing and regulatory regime administered by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).[109][110]

In 1959, Congress amended the AEA to give the states greater authority over nuclear energy regulation. The 1959 Amendments allowed states to assume responsibility over certain nuclear materials as long as their regulations were “coordinated and compatible” with federal requirements.162 While the 1959 Amendments reserved certain key authorities to the federal government, they also affirmed the states’ authority to regulate “activities for purposes other than protection against radiation hazards.”[111] Congress reorganized the administrative framework surrounding these regulations in 1974, when it replaced the AEC with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).[112]

The Supreme Court has held that, although this regulatory scheme preempts the field of nuclear safety regulation, certain state regulations of nuclear power plants that have a non-safety rationale fall outside this preempted field.

The Court identified this distinction in Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v. State Energy Resources

Conservation & Development Commission, where it held that federal law did not preempt a California [113]statute regulating the construction of new nuclear power plants.165 The California statute conditioned the construction of new nuclear power plants on a state agency’s determination concerning the availability of adequate storage facilities and means of disposal for spent nuclear fuel.166 In challenging this statute, two public utilities contended that federal law made the federal government the “sole regulator of all matters nuclear.”167

The Supreme Court rejected this argument, reasoning that the relevant statutes reflected

Congress’s intent to allow states to regulate nuclear power plants for non-safety purposes.168 The Court then concluded that the California law was not preempted because it was motivated by concerns over electricity generation and the economic viability of new nuclear power plants—not a desire to intrude into the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation.169

In addition to holding that the AEA does not preempt all state statutes and regulations concerning nuclear power plants, the Court has upheld the availability of certain state tort claims related to injuries sustained by power plant employees.

In Silkwood v. Kerr-McGee Corp., the Court upheld a punitive damages award against a nuclear laboratory arising from an employee’s injuries from plutonium contamination.170 The Court rejected the laboratory’s argument that the damages award impermissibly punished and deterred conduct related to the preempted field of nuclear safety.[114] In rejecting this argument, the Court observed that Congress had not provided alternative federal remedies for persons injured in nuclear accidents.[115] This omission was significant, the Court reasoned, because it was “difficult to believe” that Congress would have removed all judicial recourse from plaintiffs injured in nuclear accidents without an explicit statement to that effect.[116]

The Court also reasoned that Congress had assumed the continued availability of state tort remedies when it adopted a 1957 amendment to the AEA.[117] Under the relevant amendment, the federal government partially indemnified power plants for certain liabilities for nuclear accidents.

- 461 U.S. 190, 216 (1983).

- at 194.

- at 205.

- at 213–16. In its 2019 decision in Virginia Uranium, Inc. v. Warren, the Court clarified that AEA preemption will depend on this type of inquiry into the motivations of a challenged state law only when the state law implicates a “core federal power” reserved to the NRC. 139 S. Ct. 1894, 1904 (2019) (Gorsuch, J., lead opinion); id. at 1909 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in the judgment). In that case, the Court held that federal law did not preempt a Virginia statute banning the mining of uranium—a radioactive metal used in the production of nuclear fuel. See id. at 1900 (Gorsuch, J., lead opinion); id. at 1912 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in the judgment). Under the AEA and its subsequent amendments, the NRC has the authority to regulate the milling, transfer, use, and disposal of uranium, but not uranium mining conducted on private lands. See id. at 1900 (Gorsuch, J., lead opinion). In upholding the Virginia mining ban, a majority of the Court declined to evaluate the state’s underlying motivation, explaining that such an inquiry is appropriate (if at all) only when state law regulates an activity related to the NRC’s “core federal powers” under the AEA. See id. at 1904 (Gorsuch, J., lead opinion); id. at 1912–14 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in the judgment). While the Court interpreted Pacific Gas as recognizing that the construction of nuclear power plants involves one of these “core federal powers,” a majority of the Justices agreed that uranium mining does not implicate similar federal authorities because it falls outside the NRC’s jurisdiction. See id. at 1904 (Gorsuch, J, lead opinion); id. at 1912 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in the judgment). The Court accordingly relied on this distinction to uphold the Virginia law without evaluating its underlying purpose.

According to the Court, this [118]scheme reflected an assumption that plaintiffs injured in such accidents retained the ability to bring tort claims against the power plants.175

The Supreme Court applied this reasoning from Silkwood six years later in English v. General Electric Co., where it held that federal law did not preempt state tort claims alleging that a nuclear laboratory had retaliated against a whistleblower for reporting safety concerns.176

In allowing the claims to proceed, the Court rejected the argument that federal law preempts all state laws that affect plants’ nuclear safety decisions. Rather, the Court explained that a state law must have a “direct and substantial” effect on such decisions in order to fall within the federally preempted field of nuclear safety regulation.[119] While the Court acknowledged that the relevant tort claims may have had “some effect” on safety decisions by making retaliation against whistleblowers more costly than safety improvements, it concluded that such an effect was not sufficiently “direct and substantial” to render the claims preempted.[120]

In making this assessment, the Court relied on Silkwood, where it held that the relevant punitive damages award fell outside the field of nuclear safety regulation despite its likely impact on safety decisions.[121] Because the Court concluded that the type of damages award at issue in Silkwood affected safety decisions more directly and “far more substantially” than the whistleblower’s retaliation claims, it held that the retaliation claims were not preempted.[122]

Takeaways

A determination that federal law preempts a field has powerful consequences, displacing even state laws and regulations that are consistent with or complementary to federal law.[123] Because of these effects, the Supreme Court has cautioned against overly hasty inferences that Congress has occupied a field.[124] The Court has rejected the argument that the comprehensiveness of a federal regulatory scheme is sufficient to conclude that federal law occupies a field, explaining that Congress and federal agencies often adopt “intricate and complex” laws and regulations without intending to assume exclusive regulatory authority over the relevant subjects.[125]

The Court has sometimes relied on legislative history and statutory structure—in addition to the comprehensiveness of federal regulations—in assessing field preemption arguments.184 It is unclear, however, to what extent the Court might rely on even these sources in future cases.[126][127]

The Court has also adopted a narrow view of the scope of certain preempted fields. For example, the Court has rejected the proposition that federal nuclear energy regulations preempt all state laws that affect the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation. Rather, the Court has explained that, when a core federal power is not at issue, state laws fall within that field only if they have a “direct and substantial” effect on it.186

As a corollary to this principle, the Supreme Court has held that—in certain contexts—generally applicable state laws are more likely to fall outside a federally preempted field than state laws that “target” entities or issues within the field. In Oneok, Inc. v. Learjet, Inc., for example, the Court held that state antitrust claims against natural gas pipelines fell outside the preempted field of interstate natural gas wholesaling because the relevant state antitrust law was not “aimed” at natural gas companies and instead applied broadly to all businesses.187

Finally, the Court’s case law underscores that Congress can narrow the scope of a preempted field with explicit statutory language. In Pacific Gas, for example, the Court held that the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation did not encompass state laws motivated by non-safety concerns based in part on a statutory provision disavowing such an intent.[128] While the Court has subsequently narrowed the circumstances in which it will apply Pacific Gas’s purpose-centric inquiry to state laws affecting nuclear energy,189 it has reaffirmed the general principle that Congress can circumscribe a preempted field’s scope with non-preemption clauses.[129]

Conflict Preemption

Federal law also impliedly preempts conflicting state laws.[130] The Supreme Court has identified two subcategories of conflict preemption. First, federal law impliedly preempts state law when it is impossible for regulated parties to comply with both sets of laws (impossibility preemption).[131] Second, federal law impliedly preempts state laws that pose an obstacle to the “full purposes and objectives” of Congress (obstacle preemption).193 The two subsections below discuss these subcategories of conflict preemption.

Impossibility Preemption

The Supreme Court has held that federal law preempts state law when it is impossible to comply with both sets of laws.[132] To illustrate this principle, the Court has explained that a hypothetical federal law forbidding the sale of avocados with more than 7% oil content would preempt a state law forbidding the sale of avocados with less than 8% oil content, because avocado sellers could not sell their products and comply with both laws.[133]

The Court has characterized impossibility preemption as a “demanding defense,”[134] and its case law on the issue is not as well developed as other areas of its preemption jurisprudence.[135][136] Even so, the Court has addressed impossibility preemption in two decisions concerning prescription drug labeling.

Generic Drug Labeling

In PLIVA, Inc. v. Mensing and Mutual Pharmaceutical Co. v. Bartlett, the Supreme Court held that federal regulations of generic drug labels preempted certain state law claims brought against generic drug manufacturers because it was impossible for the manufacturers to comply with both federal and state law.198

In both cases, plaintiffs alleged that they suffered adverse effects from certain generic drugs and argued that the drugs’ labels should have included additional warnings.[137] In response, the drug manufacturers argued that the Hatch-Waxman Amendments (Hatch-Waxman) to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act preempted the state law claims.[138]

Under Hatch-Waxman, drug manufacturers can secure Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for generic drugs by demonstrating that they are equivalent to a brand-name drug already approved by the FDA.[139] In doing so, the generic drug manufacturers need not comply with the FDA’s standard preapproval process, which requires extensive clinical testing and the development of FDA-approved labeling.[140] They must, however, ensure that the labels for their drugs are the same as the labels for corresponding brand-name drugs, meaning that generic manufacturers cannot unilaterally change their labels.[141]

In both PLIVA and Bartlett, the Court held that the Hatch-Waxman Amendments preempted the relevant state law claims because it was impossible for the generic drug manufacturers to comply with both federal and state law.204 The Court reached this conclusion because federal law prohibited generic manufacturers from unilaterally altering their labels, while the state law claims depended on the existence of a duty to make such alterations.[142]

In reaching this conclusion in PLIVA, the Court rejected the argument that it was possible for manufacturers to comply with both federal and state law by petitioning the FDA to impose new labeling requirements on the corresponding brand-name drugs.[143] The Court rejected this argument on the grounds that impossibility preemption occurs whenever a party cannot independently comply with both federal and state law without seeking “special permission and assistance” from the federal government.[144]

Similarly, in Bartlett, the Court rejected the argument that it was possible for generic drug makers to comply with both federal and state law by refraining from selling the relevant drugs. The Court rejected this “stop-selling” argument on the grounds that it would render impossibility preemption “all but meaningless.”[145][146] As a result, an evaluation of whether it is possible to comply with both federal and state law must presuppose some affirmative conduct by the regulated party.

Despite its decisions in PLIVA and Bartlett, the Supreme Court has rejected impossibility preemption arguments made by brand-name drug manufacturers, who are entitled to unilaterally strengthen the warning labels for their drugs. In Wyeth v. Levine, the Court held that federal law did not preempt a state law failure-to-warn claim brought against a branded drug manufacturer, reasoning that it was possible for the manufacturer to strengthen its label for the drug without FDA approval.209

Obstacle Preemption

Federal law also impliedly preempts state laws that pose an “obstacle” to the “full purposes and objectives” of Congress.[147] In its obstacle preemption cases, the Supreme Court has held that state law can interfere with federal goals by frustrating Congress’s intent to adopt a uniform system of federal regulation; conflicting with Congress’s goal of establishing a regulatory “ceiling” for certain products or activities; or by impeding the vindication of a federal right.[148]

The Court has also cautioned, however, that obstacle preemption does not justify a “freewheeling judicial inquiry” into whether state laws are “in tension” with federal objectives, as such a standard would undermine the principle that “it is Congress rather than the courts that preempts state law.”[149]

The subsections below discuss a number of cases in which the Court has held that state law poses [150]an obstacle to the accomplishment of federal goals.

Foreign Sanctions

The Supreme Court has concluded that state laws can pose an obstacle to the accomplishment of federal objectives by interfering with Congress’s choice to concentrate decision making in federal authorities.

The Court’s decision in Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council illustrates this type of conflict between state law and federal policy goals.213 In Crosby, the Court held that a federal statute imposing sanctions on Burma preempted a Massachusetts statute that restricted state agencies’ ability to purchase goods or services from companies doing business with Burma.[151]

The Court identified several ways in which the Massachusetts law interfered with the federal statute’s objectives. First, the Court reasoned that the Massachusetts law interfered with Congress’s decision to provide the President with the flexibility to add or waive sanctions in response to ongoing developments.[152]

Second, the Court explained that, by penalizing certain individuals and conduct that Congress explicitly excluded from federal sanctions, the Massachusetts statute interfered with the federal statute’s goal of limiting the economic pressure imposed by the sanctions to “a specific range.”[153] In identifying this conflict, the Court rejected the state’s argument that its law shared the same goals as the federal statute. Instead, the Court reasoned that the additional sanctions imposed by the state law would undermine Congress’s intended “calibration of force.”[154]

Third, the Court concluded that the Massachusetts law undermined the President’s capacity for effective diplomacy by compromising his ability “to speak for the Nation with one voice.”[155]

Automobile Safety Regulations

The Supreme Court has concluded that some federal laws and regulations evince an intent to establish both a regulatory floor and ceiling for certain products and activities. The Court has interpreted certain federal automobile safety regulations, for example, as not only imposing minimum safety standards on carmakers, but as insulating manufacturers from certain forms of stricter state regulation as well.

In Geier v. American Honda Motor Co., the Court held that the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act (NTMVSA) and associated regulations impliedly preempted state tort claims alleging that an automobile manufacturer had negligently designed a car without a driver’s side airbag.219 While the Court rejected the argument that the NTMVSA expressly preempted the state law claims,[156] it reasoned that the claims interfered with the federal objective of giving car manufacturers the option of installing a “variety and mix” of passive restraints.221

The Court discerned this goal from, among other things, the history of the relevant regulations and Department of Transportation (DOT) comments indicating that the regulations were intended to lower costs, incentivize technological development, and encourage gradual consumer acceptance of airbags, rather than impose an immediate requirement.[157] The Court thus held that the NTMVSA impliedly preempted the state law claims because they conflicted with these federal goals.[158][159]

The Court has rejected, however, the argument that federal automobile safety standards impliedly preempt all state tort claims concerning automobile safety. In Williamson v. Mazda Motor of America, Inc., the Court held that a different federal safety standard did not preempt a state law claim alleging that a carmaker should have installed a certain type of seatbelt in a car’s rear seat.224

While the regulation at issue in Williamson allowed manufacturers to choose between two seatbelt options, the Court distinguished the case from Geier on the grounds that the DOT’s decision to offer carmakers a choice was not a “significant” regulatory objective.[160] Specifically, the Court reasoned that the state tort action did not conflict with the purpose of the relevant federal regulation, because the DOT’s decision to offer manufacturers an option was based on relatively minor design and cost-effectiveness concerns.[161][162]

Federal Civil Rights

The Supreme Court has also held that state law can pose an obstacle to federal goals where it impedes the vindication of federal rights.

In Felder v. Casey, the Court held that 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (Section 1983)—which provides individuals with the right to sue state officials for federal civil rights violations—preempted a state statute adopting certain procedural rules for bringing Section 1983 claims in state court.227 The state statute required Section 1983 plaintiffs to provide government defendants 120 days’ written notice of the circumstances giving rise to their claims, the amount of their claims, and their intent to bring suit.[163]

The Court held that federal law preempted these requirements because their purpose and effect conflicted with Section 1983’s remedial objectives.[164] Specifically, the Court reasoned that the requirements’ purpose of minimizing the state’s liability conflicted with Section 1983’s goal of providing relief to individuals whose constitutional rights are violated by state officials.[165] The

Court also concluded that the state statute’s effects interfered with federal objectives because the statute’s enforcement would result in different outcomes in Section 1983 litigation based on whether a claim was brought in state or federal court.[166]

Takeaways

The Supreme Court has held that state law can conflict with federal law in a number of ways.

State law can conflict with federal law when it is impossible to comply with both sets of laws.

While the Court has characterized this type of impossibility preemption argument as a “demanding defense,”[167] its decisions in PLIVA and Bartlett arguably extended the doctrine’s scope.[168] In those cases, the Court made clear that impossibility preemption remains a viable defense even in instances in which a regulated party can petition the federal government for permission to comply with state law[169] or stop selling a regulated product altogether.[170]

State law can also conflict with federal law when it poses an obstacle to federal goals. In evaluating congressional intent in obstacle preemption cases, the Court has relied upon statutory text,[171] structure,237 and legislative history238 to determine a statute’s preemptive scope.

Relying on these indicia of legislative purpose, the Court has held that state laws can pose an obstacle to federal goals by interfering with a uniform system of federal regulation,[172] imposing stricter requirements than federal law (where federal law evinces an intent to establish a regulatory ceiling),[173] or by impeding the vindication of a federal right.[174]

While obstacle preemption has played an important role in the Court’s preemption jurisprudence since the mid-20th century, recent developments have called the scope of the doctrine into question. Commentators have noted the tension between increasingly popular textualist theories of statutory interpretation (which generally reject extratextual evidence as a possible source of statutory meaning) and obstacle preemption doctrine (which potentially requires courts to consult such evidence).[175]

Identifying this possible inconsistency, Justice Thomas has categorically rejected the Court’s obstacle preemption jurisprudence, criticizing the Court for “routinely invalidat[ing] state laws based on perceived conflicts with broad federal policy objectives, legislative history, or generalized notions of congressional purposes that are not embodied within the text of federal law.”243

Justice Thomas’s skepticism toward obstacle preemption arguments has drawn additional support in recent cases, especially from Justice Gorsuch. In the Court’s decision in Virginia Uranium, Inc. v. Warren, Justice Gorsuch authored an opinion joined by Justices Thomas and Kavanaugh in which he rejected the proposition that implied preemption analysis should appeal to “abstract and unenacted legislative desires” not reflected in a statute’s text.[176]

While Justice Gorsuch did not there explicitly endorse a wholesale repudiation of obstacle preemption, he later joined Justice Thomas’s call for the Court to abandon its “purposes and objectives” preemption jurisprudence in a 2020 concurring opinion.[177] Although skepticism toward obstacle preemption arguments has drawn additional support in recent Supreme Court cases, to date it has remained a minority view.

— Footnotes —

[1] See Alan Untereiner, The Defense of Preemption: A View From the Trenches, 84 TUL. L. REV. 1257, 1262 (2010) (arguing that the “multiplicity of government actors below the federal level virtually ensures that, in the absence of federal preemption, businesses with national operations that serve national markets will be subject to complicated, overlapping, and sometimes even conflicting legal regimes”); Brief for the Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America as Amicus Curiae at 20, Geier v. Am. Honda Motor Co., No. 98-1811 (U.S. Nov. 19, 1999), 1999 WL 1049891 (arguing that “common-law decision making is notoriously ill-suited to the establishment of nationwide standards that strike the proper balance among the multitude of societal interests at stake in a particular regulatory setting”).